“Power concedes nothing without a demand.” -Frederick Douglass

Unions Rising

There’s a rumor going around that for new Walmart store employees, job orientation includes advice on how to access food stamps and other social services while employed with the company. Rumor or not, the corporate giant, like McDonald’s and other stores and fast-food chains, employs thousands who receive food stamps and Medicare, according to a 2020 report by the non-partisan Government Accountability Office. Yet, in 2021, the salary of the CEO of McDonalds was $20 million. The same year, the CEO of Walmart received a $3.1 million raise for a salary of $25.7 million.

You have to wonder what they do to deserve all that while ground-level employees depend on the social safety net. These are huge companies, employing millions of workers who—without the benefit of a labor union to fight for salaries, wages, benefits, and working conditions—find themselves struggling to make ends meet. In fact, companies like these actively thwart union organizing with old and new union-busting techniques. McDonald’s, for example, has a team of intelligence analysts in Chicago and London tracking Fight for $1 activists. According to Vice, these analysts spend their time “tracking workers who may be involved in activist groups advocating for higher wages, better working conditions, and the right to join unions, such as Fight for $15 campaign and its financer the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the second largest labor union in the United States.”

On the other hand, Walmart prefers old school. In 2000, rather than collaborate with newly unionized butchers in the meat department of one Texas store, the company shut down the department at that store and 179 others, leaving all the butchers jobless and communities with only pre-packaged meats.

At multi-billion dollar corporations Starbucks and Amazon, the CEOs rake it in. Starbucks’ CEO makes $20.4 million. At Amazon, the CEO makes $212 million—that’s about 6,500 times the median Amazon worker salary of $32,855. It’s inequities like this that have rightly fueled indignation among workers—and led to increases in labor organizing and power.

Labor Organizes: A Primer

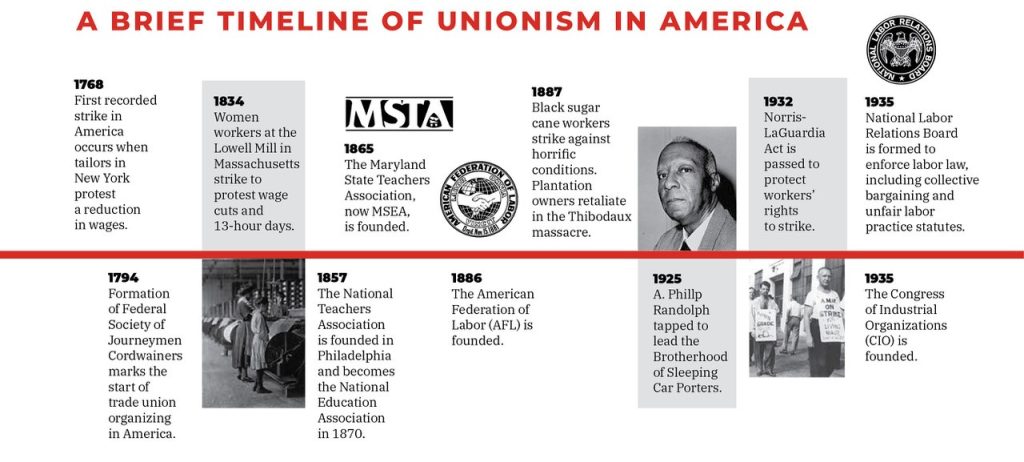

The first recorded strike in America was in 1768 when New York City tailors protested a wage cut. In 1834, women workers at the Lowell Mill in Massachusetts bravely protested grueling 13-hour days, the first of many women-led protests. In 1887, the protests of Black workers against the living and working conditions on Louisiana’s notorious sugar cane plantations were met with a murderous mob of white owners who killed 60 farmworkers. It would be years before national labor reform would come about and longer for equal representation for women, immigrants, and Black and Brown workers.

National labor organizing advanced in large part due to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and its president, Samuel Gompers. Gompers, an immigrant from London who followed his father into the cigar-rolling trade, led New York City’s Cigar Makers International Union from 1875–1896, and then helped found the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU). The FOTLU reorganized as the AFL in 1886, with Gompers elected as president, a position he kept for almost 40 years.

Gompers’ vision of labor unions was threefold: 1) restrict union membership to wage earners, not a more community-based organization open to employers as the Knights of Labor (an earlier reform effort) allowed; 2) a “pure and simple unionism” focused on pragmatic concerns like wages, hours, and grievance procedures; and 3) political non-partisanship— mobilize members around parties and candidates that support the union’s agenda.

During the rise of the AFL, landmark strides were made in legislating workers’ protections. The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 was passed, giving employees the right to strike and boycott. In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, providing basic worker protections like minimum wage, overtime pay, and basic child labor laws.

The powerful AFL and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) merged after years of bitter rivalry in 1955. The CIO was founded in 1935 and, while leadership and many skilled construction and industrial trades jobs remained out of reach for minorities and women, the CIO actively organized industrial workers no matter their race or heritage, according to the National Archives Prologue Magazine article “African Americans and the Labor Movement.”

The CIO undoubtedly influenced the new AFL-CIO’s role in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1965. In 1960, then president of the AFL-CIO George Meany said, “What we want for ourselves, we want for all humanity” and soon sought counsel from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on how they could work together. King’s proposal was that the AFL-CIO invest pension assets in housing as a way to lessen economic inequality. The AFL-CIO then established an Investment Department to guide union pension funds to be socially responsible investors. The AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust was one of the first socially responsible investment funds in the U.S. and now has assets of more than $4.5 billion.

Educator Unions Seen and Heard: Click here to see how educator unions across the state are working hard for fair contracts and pro-public education elected officials.

It should be noted that while Gompers and the hard work of labor organizers and theorists paved the way for organized labor, these unions were, through the 19th century and well into the 20th, made up of mostly white men—American born and Protestant, skilled in the trades, and able to pay union dues. Blacks, women, and Italian and Irish immigrants were excluded. It was the cigar makers in 1867 who first welcomed Black and women workers and in 1912, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers began to accept women as telephone operators. And in 1925, A. Philip Randolph was tapped to lead the all-Black service staff of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; 10 years later they won the right to collectively bargain.

Randolph was just getting started in his fight for Black workers. In 1940, President Roosevelt refused to issue an executive order to ban discrimination against Black workers in the defense industry. When Randolph threatened to organize 100,000 “loyal Negro American citizens” to march on Washington, Roosevelt capitulated and issued the order, which stated: “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” Later Randolph forced Harry Truman to end military segregation by threatening to hold the Black vote. In 1963, he was made chair of the March on Washington.

More Recent History

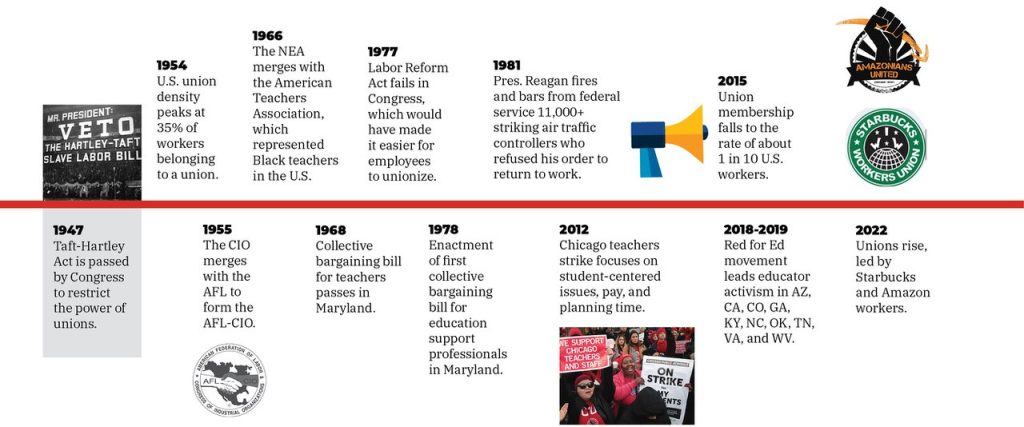

Unions, once the watchdog of a rising middle class, suffered in the late 20thcentury. The middle class floundered as blue collar jobs and manufacturing were outsourced to cheaper labor in other countries. Those types of steady jobs have not returned nor have they been replaced. Many working class families, once thriving and moving up the ladder of education and wealth thanks to the bargaining power of union members, have been left looking for work, falling victim to despair and all that comes with it.

But every community needs schools and educators, so it’s not surprising that educators’ unions, still large, influential, organized, and largely white collar emerged as the labor leaders of the early 21st century. Just this year, major campaigns in Minnesota, California, and Illinois demanded better funding for salaries, mental health supports, and health and safety protocols for K–12 schools. Underfunding and underprioritizing public schools is commonplace around the country as states, districts, and politics undermine students and communities. The most underserved communities are, of course, the most vulnerable to this trend.

“We’ve been talking about this for years. This is not new,” NEA President Becky Pringle told Vox. “And here’s the reality. When you consistently underfund our public schools, it compounds.” These actions follow the momentous pre-covid Red for Ed wave of educator activism in 2018–2019. Then, an uprising across the country in red and blue states began in West Virginia and spread to Arizona, California, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and a school bus driver strike in Georgia. Outcomes were promising for some with raises of up to 20% (Arizona), a $6,000 raise for teachers and $1,250 raise for support staff (Oklahoma), and a reduction in class sizes (two California districts), but in Georgia, seven bus drivers were fired. The educators struck a nerve in workers across the country. Unions were in the news—stories, photos, and memes showed emboldened workers. Suddenly, people who looked like YOUR kid’s teacher, YOUR mom, YOUR dad, YOUR sister or brother were marching, shouting, carrying signs, and wearing loud t-shirts. It looked like something YOU could do. In fact, it looks a little like educators schooled Americans on how to take control of their working life, using grassroots organizing, public pressure, and worker-to- worker conversations to stand up to inequities and unfair systems.

Activism Spills Over—Big Time

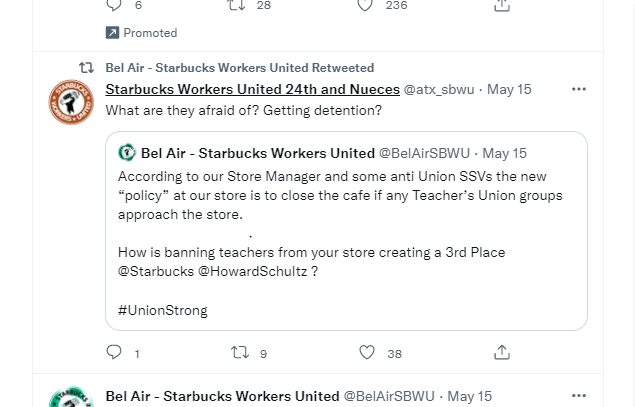

One day in late May, on Twitter alone, notices about new union organizing efforts or successes were tweeted from Starbucks stores that included: Dallas-Fort Worth; Leesburg, VA; Seattle; Cottonwood Heights, UT; Chicago; New York City; Salem, OR; Louisville; Pittsburgh; Knoxville; and Birmingham. The workers in more than 250 additional Starbucks stores have filed with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to have a union vote. At least 30% of workers must sign a petition and file it with the NLRB and with its approval, preparation can begin to hold a yes or no vote to unionize. The election to unionize then requires a vote of 50% + 1 to unionize.

there won their union vote on June 1 and are now affiliated with Starbucks Workers United.

Starbucks Workers United took off in late 2021 in Buffalo, NY when workers at two stores there voted to unionize in a true grassroots movement. At press time, workers in 135 Starbucks stores in 28 states have won their union elections since December—many with unanimous votes and all affiliated with Starbucks Workers United (part of Workers United, an affiliate of SEIU). Six Starbucks stores in Maryland have already unionized in Baltimore (N. Charles St.), Bel Air, Linthicum, Olney, Stevensville, and White Marsh.

Why unionize? “Partners,” as corporate calls them are anything but, they say. In a letter to CEO Howard Schultz, Bel Air workers wrote, “For 50 years you have called us ‘partners,’ but for 50 years you have not once treated us as partners in the workplace. … One of Starbucks’ key morals is to challenge the status quo and that is what we are doing today in writing this letter.” The letter lists their grievances, which mirror many of those in stores fighting for unionization—raises promised but not received; lax safety protocols during covid; inadequate training; reduced hours; inadequate staffing; and inadequate protocols for the managing of disruptive, racist, or rude customers.

“I was following the Starbuck’s workers’ unionization efforts and was so excited when I saw that our local store had joined the fight. I encouraged them each time I was there and soon my colleagues joined me,” said Harford County Education Association (HCEA) member Abby Bennett who staged a protest in front of the Bel Air store with HCEA colleagues. “It was important because it’s so close to home— any union that happens in our hometown is better for all of us.”

When the first stores in Buffalo organized in late 2021, it signaled a new day for the union movement and food service workers. Historically difficult to organize due to the high employee turnover rate, these workers suffer many of the same issues that were so prevalent before the rise of unions in the 20th century—pay, benefits, health care, paid time, off, quality training, and safe working conditions. They’re also young, empathetic, diverse in race, gender, age, and education, and worried about how they can make it in a world so seemingly committed to a brutal inequality. “We’ve been forced into this world where we can’t afford anything, where we can’t afford to live,” one worker told Vox. It’s the duplicity of Starbucks corporate values that finally tipped the scale.

Thanks to the efforts of brave organizers who’ve put unions back in the news, unions are enjoying record approval ratings in the U.S. and that’s showing up in more and more union activity. According to the NLRB, union representation petitions are up 57% and unfair labor practice charges are up 14%.

Amazon Workers Win

To say Amazon is anti-union is an understatement. Just ask 33-year old organizing wunderkind Christian Smalls, whose success in organizing employees at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, NY blew the minds of both Amazon big shots and many in the organized labor movement. With $120,000 in GoFundMe donations, no organizing experience, and the full force of the second largest private employer in the country against him, Smalls and friend and former co-worker Derrick Palmer defied the odds and created the Amazon Labor Union—the first union of Amazon workers in history.

Smalls led a modest walkout in March 2020 over early covid safety conditions. Amazon’s response was near hysteria with the corporate giant calling in its “Global Response Team,” and naming an “incident commander.” The 11 executives alerted to the walkout outnumbered participants. In a clueless, repugnant slam against Smalls, Amazon’s chief referred to him as “not smart or articulate.” Then they fired him under the pretense that he had violated social distancing guidelines.

After that, he and Palmer watched as a union vote in an Amazon warehouse in Alabama, organized by the retail workers union, failed. Recognizing that traditional organizing strategies may not be the right fit for Amazon, the two began to organize from the inside out, creating, like Starbucks, a true grassroots, worker-led, independent union. Workers saw through Amazon’s unionbusting playbook of retaliation, required attendance meetings that turned into antiunion propaganda sessions, and referring to the worker-led organizers as “third-party” interlopers.

“What we were trying to say all along is that having workers on the inside is the most powerful tool,” Palmer told the New York Times. “People didn’t believe it, but you can’t beat workers organizing other workers.” When election day came, the union won—beating a $4.3 million anti-union campaign. Christian Smalls is now the president of the Amazon Labor Union and represents 8,000 employees. While workers at Amazon warehouses have not at the pace of the smaller Starbucks stores, Smalls believes their grassroots tactics are the answer.

“I can’t wait till the next campaign. I like educating, having face-to-face conversations. And I like dealing with the tough ones who are not easy to convince. Those are the best conversations because when you do get them, they end up becoming really strong leaders for the union,” he said in Interview Magazine. “So I’m looking forward to our next battle because this is a war. There’s going to be losses and casualties on both sides. But I know this is for the long haul—we’re going to continue to win and organize.”