What Passed, What Didn’t, What’s Next

And other legislative updates in this week’s Up the Street

THIS WEEK IN ANNAPOLIS

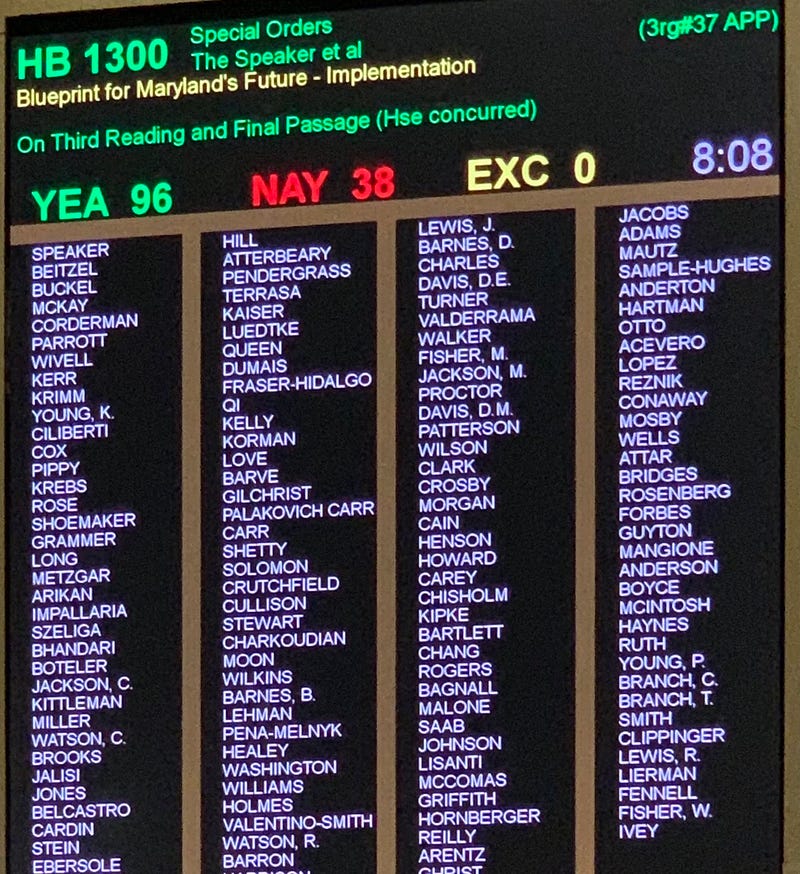

The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Passes in Shadow of Coronavirus

What would have been a day to exuberantly celebrate the passage of the most important education legislation in a generation instead was overshadowed by the widespread coronavirus infection threatening the nation. On Wednesday at 5 p.m. the historic 441st General Assembly session, like no other since the Civil War, adjourned early and returned legislators to their home districts to deal with the pandemic threat and escalating number of infections. In the haste to conclude essential business before obeying national health experts’ guidelines to avoid groups of more than 10 people, legislative leaders took up the bills they deemed most critical. Constitutionally, they are required only to pass a budget bill during the annual session, but they managed to include much more in this session, despite concluding ahead of the original April 6 Sine Die date.

On Monday just before midnight, the Senate gave final approval to the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future as the House did a week ago. Then on Tuesday evening, the House concurred with the Senate version of the bill, sending it to Governor Hogan for his action. For years we’ve fought for this transformative legislation. It is a giant win that will correct the chronic underfunding of our schools that has left the average Maryland school millions of dollars short annually and held back opportunities for our students. As many floor speeches emphasized, committing to the Blueprint is not a luxury, but a debt owed to the state’s children. The Blueprint is the most significant education bill since 2002 and implementing it well and with fidelity will be key to the future success of our state’s children and economy.

The Blueprint directly impacts early childhood education, the education profession, career and college readiness, equity in education especially for children in poverty, and statewide education accountability. The first three years of the Blueprint were set in motion by last year’s General Assembly, which increased state school funding for the current school year by $255 million, $355 million in 2020–2021, and $500 million in 2021–2022. That $1.1 billion increase is paid for out of casino revenue thanks to the 2018 passage of Question 1 (Fix the Fund), a $200 million set-aside in FY 2019, and an adjustment to online sales tax compliance. The continued support of the gaming revenues and the sales tax compliance change will be critical building blocks to the mid- and long-term ability to cover the costs associated with the Blueprint.

Equity

Also because of last year’s legislative action, more than 200 community schools have been established to close the gap between low-income students and their more affluent peers. Community schools are key to the Blueprint’s plan to restore equity in education and give every child, no matter their zip code, a great public school. In these schools, a community school coordinator establishes a set of strategic partnerships between a community school and other community resources to promote student achievement, positive learning conditions, and the well-being of students and their families by providing wraparound services. Community schools will be phased in at all schools where low-income students make up 55% or more of the student population. Personnel funding pays for a coordinator and a health services practitioner and per pupil funding will cover the costs associated with the school-specific needs assessment and plan that will deliver specific services needed to support the students and families at the school. The phase-in started this school year at schools where 80% or more of students live in poverty, and the rest will be phased in by 2025. At full phase-in, nearly one-third of schools in Maryland will become community schools — a ringing endorsement of this model and a sad statement on the levels of child poverty across the state.

Concentration of poverty funding of about $3,300 per pupil will eventually support schools where 55% percent or more of the student population lives in poverty. Those per pupil grants start in FY2022 and will phase in starting in 2022 with schools at 80% poverty to include schools with 55% poverty by 2027.

Special education funding increases throughout the phase-in of this proposal, ultimately increasing per pupil support for students receiving special education services by more than 80% per student. In state aid alone, special education funding grows by $1.2 billion from FY22 to FY30. Under the new formula and maintenance of effort changes, local governments will be responsible for the local share of special education costs as well.

Funding for students who are English language learners also increases with the new funding formula. Over the full phase-in, this at-promise factor increases state aid for education by almost $450 million. Just like the special education weight on the new formula, there is an expectation of local governments covering their share of this funding as well.

One of the most important and beneficial amendments to the bill was a new funding formula that provides relief from some of the financial obligations facing local governments. These formula amendments will result in the state absorbing a greater proportion of the increased education funding than originally projected in 17 jurisdictions: Allegany, Anne Arundel, Baltimore City, Baltimore County, Caroline, Cecil, Dorchester, Garrett, Kent, Montgomery, Prince George’s, Queen Anne’s, Somerset, Talbot, Washington, Wicomico, and Worcester.

Details of the new formula can be seen in these exhibits. Page 1 outlines the major funding areas in the Blueprint and how much state aid increases from FY22 to FY30 by year. Page 2 shows that additional state aid by year and by county. Page 3 projects how local government increases will be phased in. Page 4 reflects the formula change noted above that saved local governments money from the original proposal. Finally, page 5 projects what both state and local school aid will be in FY30 and the percentage increase that results from the phase-in of the formula by that year.

All of the funding formulas are based on a per pupil foundation amount, which increases with inflation. The starting foundation amount in next year’s budget is $7,991, and increases to $12,138 by 2033, plus inflation. Additional per pupil amounts will fund the associated programs — such as special education, English language support, and concentration of poverty — as a fixed dollar amount or percentage of the foundation amount, multiplied by the number of pupils qualifying for the additional program resource.

Career and Technical Education

The global investigation and research conducted for the Kirwan Commission demonstrated the importance of preparing students for their future in jobs that pay well. The Blueprint will expand career and technical education (CTE) to make it accessible to all high school students, regardless of their location. The target is to have 45% of graduates achieve an industry recognized occupational credential before they graduate. To accomplish this, CTE programs will expand across the state and be better woven into curriculum across grade levels. Local school systems will be charged with developing partnerships with local businesses to better integrate these programs with local economic priorities and needs.

Early Childhood Education

The early childhood education component of the Blueprint is based on the research that pre-kindergarten raises academic achievement and provides a foundation that is essential to overall academic success. The Blueprint plans to have free public pre-k available to all three- and four-year-olds below 300% of the federal poverty level. The federal poverty level is $26,200 for a family of four. So Tier 1 students at 300% or less means a student from a family of four with an income of less than $78,600. There is then a sliding cost scale for four-year-olds in families between 300% and 600% of the poverty level (Tier II). This school year there was $32 million to convert more half-day pre-k for low-income four-year-olds to full-day. This is estimated to grow to $59 million in the next school year, with further expansion once the new formula takes effect. This year the legislature amended the Blueprint phase-in schedule by three years for Tier II four-year-olds. Funding will account for both Tier I and Tier II in FY 2023, instead of 2026.

The legislation also includes significant expansion in Family Support Centers, Judy Centers, and Infant and Toddler programs that are designed to support families and students before they enter the public school system.

For the Educator: Improved Pay, Better Staffing, and Strong Voice

One of the major findings of the Kirwan Commission was the pay differential between Maryland’s educators and those in the top-performing US and international school systems. To help address the pay challenges, the Blueprint sets the expectation that teacher salaries will increase by 10% between 2019 and 2024 in order to help close the gap between Maryland and competing states. Additionally, the bill sets a starting salary for all teachers in the state to be $60,000 no later than July 1, 2026.

In addition to those pay increases for all teachers, the Blueprint creates a career ladder that offers teachers paths to advancement without having to leave the classroom for administrative or central office positions. Under the bill, National Board Certification will be a pre-requisite to climb the ladder, but existing pay scales built on education levels and years of experience will also be maintained. There are considerable financial incentives in the bill to support teachers who are or who want to become Nationally Board Certified, including $10,000 for attainment of the certification and additional minimum pay increases for maintenance and renewal every five years.

The ladder and professional standards aspects will be among the more complex features of the legislation for educators and local associations to implement, and MSEA is ready to help explain the process called for in the new law. It has the potential to raise salaries and professional status long overdue our educators, but we must make sure that educators have a strong voice in how it is implemented so that it is successful. The ladder includes benchmarks for teachers to achieve certain designations as mentor, lead, and professor.

The Blueprint phases in significant funding increases starting in FY2025 to allow for more collaboration time of educators. This time will require the hiring of more teachers and education support professionals (ESPs). The collaboration time will allow educators to work with each other, support small-group instruction, individual tutoring support, pursue job-embedded professional development, and have conferences with students and parents. Staffing increases will alleviate shortages of ESPs, particularly among paraeducators.

When it comes to educator voice, MSEA worked hard to include an amendment that assured the State Board of Education has to have concurrence from the Professional Standards and Teacher Education Board (PSTEB) for policy decisions concerning teacher certification and licensure. This was one of many areas where we fought to increase the voice of educators in both the implementation of the Blueprint and the work associated in leading the profession.

Strong Accountability

The Blueprint creates the Accountability and Implementation Board (AIB), which has the overarching responsibility to ensure quality implementation of the Blueprint, designate expert review teams who will join local educators and school boards in assessing compliance with the Blueprint, and look for ways to improve aspects of the Blueprint that are not working. We supported a successful amendment that balanced the power of members representing the Senate president, House speaker, and the governor on the AIB nominating committee and in structuring terms of service for both the nominating committee and the AIB itself.

The AIB is made up of seven members, appointed by the governor from a list of nominees presented by a six-member nominating committee. The AIB members are not paid and will serve staggered six-year terms. Collectively, this board shall reflect the geographic, racial, ethnic, cultural, and gender diversity of the state. And the board members should have a high level of knowledge and expertise in early and secondary education policy, postsecondary education policy, teaching in public schools, strategies used by top-performing states and systems around the world, leading systemic change, and financial auditing and accounting.

Into the Future

The final version of HB 1300 will post here once all of the amendments are enrolled in the final version of the bill. After hundreds of amendments, it will be important to outline all of the key phase-in dates and aspects of the bill. That will help us better understand when funding is available and when new mandates would take effect. As MSEA goes through the bill, we will continue to identify areas of concern that will likely require future legislation to address. We believe some areas lack clarity, while other areas are too prescriptive. We are worried about a desire from some to pull the plug early on implementation when only 40%-50% of the funding is phased in. But with a massive bill and undertaking like this, we will need to start the implementation before some of these issues are clearly understood and easily identifiable. We will count on educators to be on the front lines of the implementation and to work with MSEA and other education advocates to identify needed changes. We believe the legislature is committed to working with educators to get this done right.

What’s Next

The Blueprint will be presented to the governor in the coming days. Once he receives it, he will have 30 days to act. He may veto the bill, or he could sign it or let it become law without his signature. If the governor vetoes the Blueprint, the General Assembly is planning a special session in late May. Considering bipartisan supermajorities passed the bill in the legislature, we would push to ask those same legislators to vote yes again to override the veto. Whether the bill is signed or a veto is overridden before the end of June, the Blueprint would be able to take effect, as planned, on July 1, 2020 with the new formulas being implemented starting in FY22.

Following its effective date, the selection of the AIB nominating committee will begin, leading to the selection of the AIB’s seven members. The AIB is to develop a comprehensive implementation plan by February 15, 2021. Criteria for individual district implementation plans are to be ready by April 1, 2021. Each district will have a Blueprint implementation coordinator and local plans approved by the AIB by June 15, 2021.

Revenue to Pay for the Blueprint

While the first few years of the Blueprint are already paid for, legislators considered more than a dozen revenue bills to further fund the Blueprint over the next decade. The final result saw a more modest package of new revenue options to support the Blueprint and other state needs and priorities, including the immediate response to the coronavirus emergency. Future action will certainly be needed to fully fund the Blueprint through its full implementation. The revenue bills that passed this year set a revised tobacco tax including electronic tobacco products, and create a tax on gross receipts of digital advertising companies, such as Facebook and Google. Revenue from these bills has been dedicated to historically Black colleges and universities, coronavirus response, and budget stabilization over the short-term, but can help provide future resources to the Blueprint. One bill that will produce Blueprint-specific revenue is the digital downloads tax. This is not exactly a new tax, rather is a modernization of our current taxing system. It applies the sales tax more fairly to new formats of products that are already taxed, like books, music, and video games. And the final piece of the revenue puzzle relates to gaming. If voters approve a ballot measure in November, Maryland will be the latest state to offer legalized sports betting.

NEWS AND NOTES

Budget Successes

Within the adopted $47.9 billion budget for FY2021, we successfully held all dollars related to Blueprint implementation for FY21 and we maintained full actuarial pension funding as well. We also counted as a victory the reduction of the governor’s funding for the BOOST voucher program. While he sought $10.2 million for FY21, the legislature amended the amount to flat fund it at $7.6 million. The $2.6 million difference will go to Medicaid.

Built to Learn

We supported the $2.2 billion Built to Learn Act, House Bill 1. This will address the need for construction, maintenance, and repairs. Every district has examples of buildings without adequate heat, rodent infestations, poor drinking water quality, mold, and other deplorable conditions. In areas where enrollment has grown, new classroom capacity is needed. This funding commitment makes up a difference between the longstanding needs and the lack of funds. The average age of schools in the state increased by three years between 2006 and 2016.

Funding for Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Another great moment this session was the passage of House Bill 1260, to pay a long overdue debt to Maryland’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The legislation, which awaits the governor’s signature, requires the Maryland Higher Education Commission to establish the HBCU Reserve Fund and requires the governor to include in the general fund budget $57.7 million for the fund every year between 2022 through 2031, for a total of $577 million. This was a major priority for Speaker Adrienne Jones and will settle the decade-plus lawsuit between the HBCUs and the state of Maryland. This is a long overdue settlement.

Legislation Related to Discipline and Targeting Trauma in Schools

Because so many students come to our schools with unprecedented levels of trauma, we supported two bills this session. They attempted to address this issue directly: one by addressing the root causes of trauma through the trauma-informed school initiative (House Bill 277), and one by protecting educators who step into the fray during physical altercations (House Bill 802), which often involve students experiencing trauma.

HB 802, the Good Teacher Protection Act, did not pass. Establishing the Trauma-Informed Schools Initiative did and is on the governor’s desk for his signature. Trauma-informed practices taught in specialized training take into account the stresses that students and educators are bringing to school and seek to properly and effectively address how this affects the school environment. Our schools need to be safe environments where learning and healing can occur.

Coronavirus Will Affect Public, Schools, Educators for Months

All of the legislative ups and downs in this abbreviated session occurred against a backdrop of increasing urgency to address the coronavirus pandemic. Daily announcements of new restrictions changed the playing field until no members of the public were allowed in the State House, a majority of the world worked from home, and everyone mastered virtual greeting methods and adopted rigid handwashing practices. The governor has proclaimed a state of emergency and implemented dramatic measures, including school closures that affect all students and educators between now and the end of next week.

The best source for statewide coronavirus information is the State Health Department.

- Click here for a round-up of how, where, and when students in every jurisdiction in the state can get free meals while schools are closed.

- Local associations are doing great work to get clarity from school systems on current procedures and ensure that hourly workers are paid during this closure.

- For updates on MSEA events, federal regulatory issues, how to register for an absentee ballot during Maryland’s primary election that has been rescheduled for June, and more please click here.

The response to the ongoing damage to public health and the state economy from the coronavirus develops and changes hourly at the state and national level. The governor directed all state health insurers to waive coinsurance, deductibles, and preauthorization requirements associated with coronavirus testing. It is critical that anyone who meets the criteria for testing get tested right away. The General Assembly rushed to approve legislation (SB 1079/HB 1661) to deal with other potential coronavirus costs. That legislation allows the governor to transfer up to $50 million from the Revenue Stabilization Account (Rainy Day Fund) to pay costs associated with coronavirus infection response.