We Need to Improve Minority Teacher Turnover

62% of Maryland students are minorities, but only 26% of teachers are.

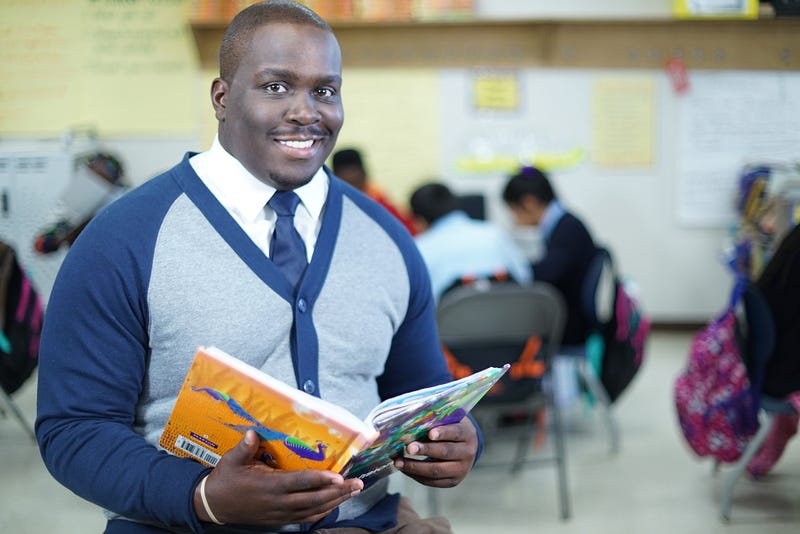

Minority teachers have the power to make their schools a better place — and be a critical role model, ally, and advocate for all students, especially minority students. In fact, research has shown that minority teachers may lead to greater academic gains by minority students and can play an important role in closing achievement gaps. A recent study found that “a disadvantaged black male’s exposure to at least one black teacher in elementary school reduces his probability of dropping out of high school by nearly 40 percent.”

“Minority students often perform better on standardized tests, have improved attendance, and are suspended less frequently (which may suggest either different degrees of behavior or different treatment, or both) when they have at least one same-race teacher.” —Brookings Institution

Minority teachers don’t just have an impact on minority students. A 2016 study found that students — no matter their race — “generally felt more supported and motivated by teachers of color.”

All this research clearly demonstrates the need to focus on recruiting and retaining minority teachers. So how has Maryland done on those scores?

Minority Teachers in Maryland

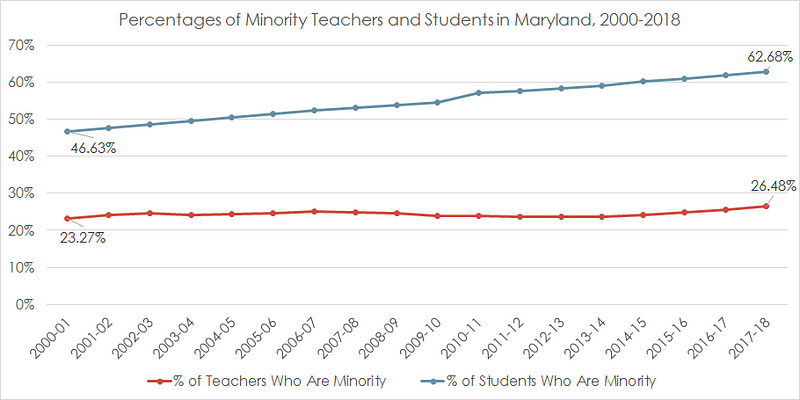

Let’s look at the last couple decades of teacher and student demographics in Maryland. Since 2000, the total number of students in Maryland public schools has increased by about 4%, or just over 40,000 students. However, the total number of minority students has increased by more than 40%, or around 162,000 students. Maryland has gone from a majority white student body (54% white in the 2000–01 school year) to majority minority (62% minority in 2017–18).

While students have grown increasingly diverse, the teacher workforce hasn’t kept pace. In the 2000–01 school year, minority teachers made up just over 23% of the workforce. Seventeen years later, that percentage has inched up by only three percentage points, to 26% of the workforce.

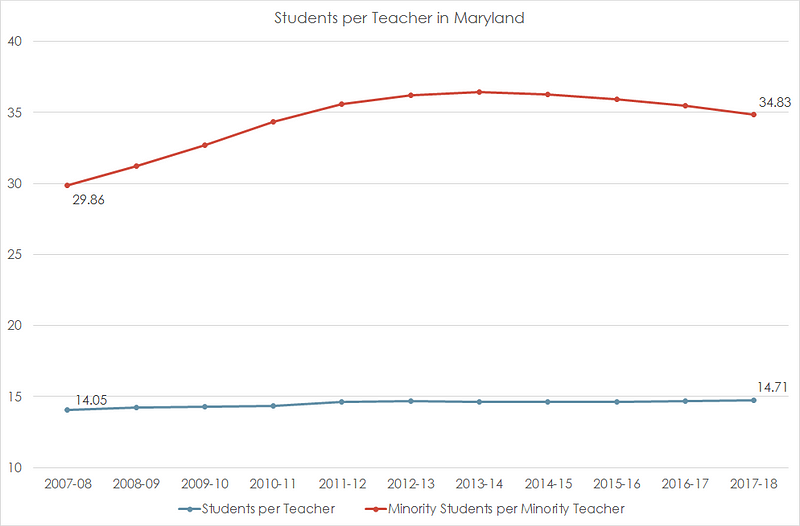

Another way to think of that number is by looking at the teacher-student ratio. In the last decade, the number of students per teacher has crept upwards to 14.71 students per teacher, as school funding stagnated and created the current $2.9 billion annual underfunding of our schools.

But the number of minority students per minority teacher — an important metric considering the positive effects that minority teachers may have for minority students — is a different story. While there are nearly 15 students per teacher, there are nearly 35 minority students per minority teacher. And that ratio has gone in the wrong direction over the last decade; ten years ago, there were about 30 minority students per minority teacher. This trend makes it harder to distribute the positive effects of minority teachers for minority students.

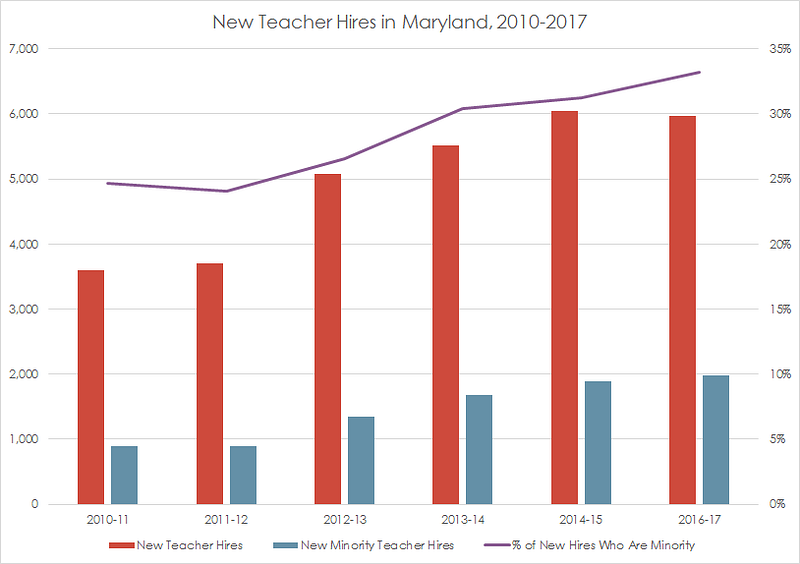

While the number of new teachers hired in Maryland who are minorities has increased since 2010 (the first year data is available publicly), minority teachers only make up about one-third of all new teacher hires. And while that number has steadily increased, hiring only tells part of the story.

The Big Problem: Retention

While recruiting enough minority teachers is part of the problem, an even larger problem is retaining minority teachers. Looking at national data, minority teachers have had significantly greater rates of turnover than white teachers. And the rate of minority teacher turnover appears to be increasing. It’s particularly acute among minority male teachers, who depart at rates 50% higher than minority female teachers (such a gender disparity does not seem to exist for white teachers).

We can amp up the focus on recruiting more minority teachers, but if we can’t keep them in classrooms then it’s a losing proposition.

What factors are driving minority teachers from classrooms? A recent study by school staffing expert Richard Ingersoll and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) found two primary factors — and they may not be what you think.

Classroom Autonomy

According to the LPI report, the strongest factor in retaining a minority teacher is their level of classroom autonomy. Classroom autonomy is usually defined as control in selecting textbooks and class materials; evaluating and grading students; selecting the content, topics, and skills to be taught; disciplining students; selecting teaching techniques; and determining homework amounts.

“A one-unit difference in reported teacher classroom autonomy (on a four-unit scale) was associated with a 40% difference in the odds of a minority teacher departing.” — “Minority Teacher Recruitment, Employment, and Retention: 1987 to 2013,” Learning Policy Institute

Unfortunately, teacher autonomy is a huge problem in Maryland. Another recent report by the Learning Policy Institute found that Maryland was ranked second-lowest in the country — ahead of only Florida — in teacher autonomy.

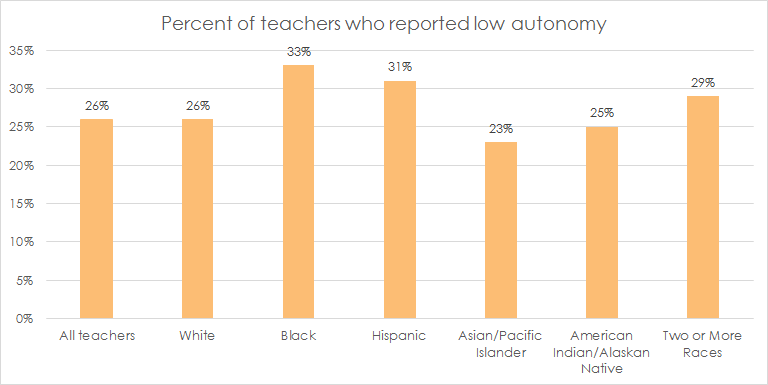

This disappointing rank is based on data from the School and Staffing Survey, a poll of more than 37,000 teachers conducted by the federal National Center for Education Statistics. The survey found that most minority teachers reported having lower autonomy than white teachers: 26% of white teachers reported having low autonomy, while 33% of Black and 31% of Hispanic teachers reported low autonomy.

Teacher Voice

The other major factor impacting minority teacher retention identified by LPI’s research is teachers having a voice in school decisions. As the report’s authors put it: “schools with higher levels of decision-making influence had lower levels of turnover for both nonminority and minority teachers…and especially so for minority teachers.”

“A one-unit increase in reported faculty influence between schools (on a four-unit scale) was associated with a 37% decrease in the odds of a minority teacher departing.” — “Minority Teacher Recruitment, Employment, and Retention: 1987 to 2013,” Learning Policy Institute

What Didn’t Make the Cut?

LPI’s research found little relationship between the demographics of a school and the likelihood of a minority teacher staying in the profession. Similarly, researchers found that retention is not greatly influenced by how many students in poverty or minority students attend the school, how many minority teachers work in the school, or whether the school is in an urban or suburban setting. While higher salaries are associated with lower turnover for all teachers regardless of race, this effect is not substantially stronger for minority teachers.

Improving Minority Teacher Retention

The evidence is clear in the benefits that minority teachers bring to classrooms and what helps keep them there. The Kirwan Commission’s initial work to increase planning and collaboration time and improve school leadership quality could play key roles in enhancing teacher autonomy and teacher voice, particularly for minority teachers. But we will need to keep pushing — with the Kirwan Commission and legislature all the way to the building level — to deliver the working conditions that will help solve the minority teacher retention problem, and benefit all educators and students in the process.