Thornton Worked — and So Will the Blueprint

Asthe Maryland General Assembly begins critical discussions on the Kirwan Commission’s school policy and funding plan — dubbed the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future — some have argued that Maryland’s last major investment in public education, the Thornton Bridge to Excellence Act, was a failure.

The Washington Post Editorial Board — conservative when it comes to education policy — wrote: “The state’s previous experience…demonstrated the shortcomings, if not outright failure, of increased education expenditures to produce better outcomes.”

In a letter sent to legislative leaders, Gov. Hogan wrote, “Without strong accountability, we’ll be doomed to experience the same failures of the Thornton initiative…the central question is: are Maryland schools better today than they were in 2002?”

But did Thornton really fail?

It’s All About NAEP

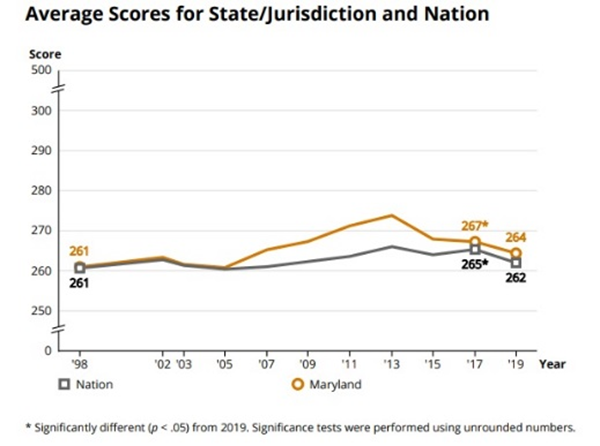

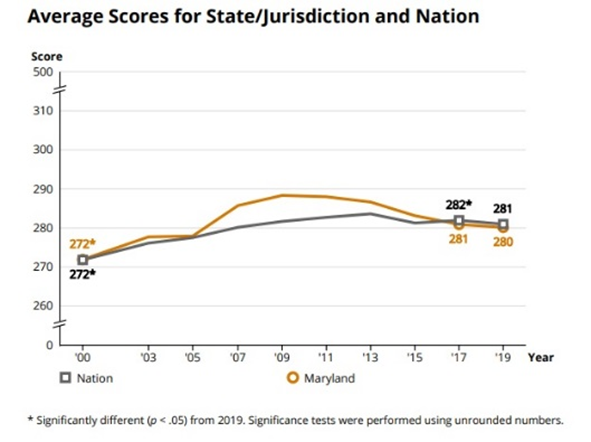

The data tells a clear story — Thornton worked. As funding has leveled off post-Thornton, student achievement has declined.

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)— known as America’s Report Card — convincingly demonstrates this. NAEP is the only standardized test given to a representative sample of students in all 50 states and therefore can be used to compare student learning across the country. So while there are many measures of student outcomes, education reform debates usually use NAEP to compare math and reading performance between states.

If Maryland schools were ever mediocre, it was in 2003. America’s Gradebook ranked Maryland as 31st in the nation for that year, despite Maryland ranking 17th in the nation for most per pupil funding.

Then Thornton implementation happened between 2003 and 2008. In 2005, Maryland moved up to 26th. In 2007, the state ranked 15th. In 2009, Maryland was all the way up to 6th. Maryland then ranked 4th in 2011 and 3rd in 2013. NAEP showed a tremendous improvement relative to the rest of the country thanks to a decade of increased education funding.

Prior to Thornton, Maryland scores were exactly the national average. As Thornton implementation kicked into high gear, scores rose — and outpaced national growth. And once the effects of funding leveling off set in, NAEP scores ticked back down and have returned to the neighborhood of the national average.

Nearly a decade of level funding and the consequential ground lost in student achievement has led critics to say that Thornton didn’t move the needle on student achievement. Nothing could be further from the truth — it’s because funding didn’t keep up that we couldn’t sustain the improvements that Thornton delivered.

But Achievement Gaps Still Exist

Thornton was about both funding adequacy and equity. Gov. Hogan’s letter claims the black-white student proficiency rate gap has widened since Thornton, but that would require measuring between two different assessments (in the early 2000s, Maryland gave the MSPAP test; in 2017–2018 it gave the PARCC test) and two different learning standards (Common Core is a much higher bar than the standards used before). There’s no valid way to do that.

Once again, the best data to measure whether Maryland has narrowed achievement gaps — both for race and income — is from NAEP. That data suggests there is little statistically significant movement in achievement gaps for black, Hispanic, or low-income students.

There is a slight narrowing for black and low-income students in all four tests (4th grade reading, 4th grade math, 8th grade reading, and 8th grade math), while there is a slight widening for Hispanic students. This means that as achievement rose overall, it rose at similar rates in student subgroups — with black and low-income students seeing marginally greater improvement than the average student and Hispanic students seeing marginally smaller improvement.

No doubt, large gaps remain — at least based on standardized test scores — and a new financial investment would have to be targeted in a different way than the Thornton plan to have a larger impact on equity in outcomes. That’s exactly what Kirwan and the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future propose to do through its additional funding for schools in communities of concentrated poverty, expansion of community schools, and more. It’s also important to remember that no education-only plan will close these gaps. Research shows that school-based solutions can only solve part of the disparities in student learning outcomes. The rest has to be solved by tackling economic inequality and institutional racism elsewhere in society.

The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Will Build on Thornton’s Progress

While the Thornton Plan vaulted Maryland schools from mediocre to top ten, our schools can and must do more for students if our state has any chance of leading the nation — and competing internationally — in attracting jobs and businesses of the future in a rapidly changing economy. The funding formula has not been updated to reflect much higher learning standards adopted in recent years, and it continues to fund wealthier districts at a higher level than school systems with more child poverty.

The Kirwan Commission has spent three years incorporating into their recommendations the programs and policies that have worked in the highest-performing states and countries. Their recommendations include proven measures such as expanding career technical education, community schools, and pre-k; increasing educator pay; hiring more educators to increase individual attention for students and to expand teacher planning and collaboration time; and providing more support for special education and mental health services.

These initiatives have moved the needle in the states and countries where they have been implemented, and the new accountability provisions in the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future will make sure that they are implemented with fidelity and produce results.

Maryland can only move to the level of top states and top international school systems if it significantly narrows achievement gaps based on race and income. That’s exactly what the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future aims to do by building on the important progress made by the Thornton Bridge to Excellence Act.