The Tipping Point: Solving the Staffing and Salary Crisis in Maryland Schools

After years of understaffing, it has finally culminated in an adverse effect on student learning.

What does $2.9 billion in annual underfunding in our schools look like? A slow-building — but now impossible to ignore — crisis of inadequate staffing levels and educator pay that has direct consequences on the quality of teaching and learning, especially in high-poverty schools. After major progress on both staffing and pay following the state’s last revision of the school funding formula in the early 2000s, the Great Recession and plateauing of education funding has prevented the resources from matching the needs. It’s reached a tipping point — one that the Kirwan Commission’s work must pull our state back from.

SOLVING THE STAFFING PROBLEM

What happens when there aren’t enough people in a school to meet the needs of its students?

Take a look at the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores (the most recent) and the oft-cited students-to-teacher ratio. NAEP, “the Nation’s Report Card,” found Maryland students ranked 25th in the country in eighth grade math.

How does this compare? Each of the three states with the smallest students-to-teacher ratio — New Jersey, Vermont, and New Hampshire — rank in the top five for eighth grade NAEP scores in math. In fact, 15 of the 25 states with better NAEP math scores than Maryland had better students-to-teacher ratios, while only four of the 24 states with lower NAEP math scores had fewer students-per-teacher.

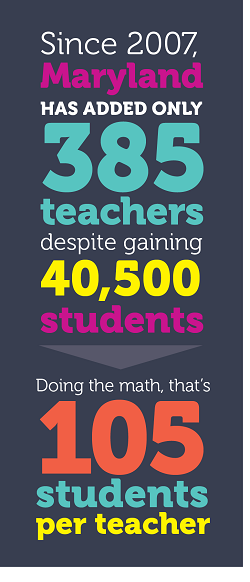

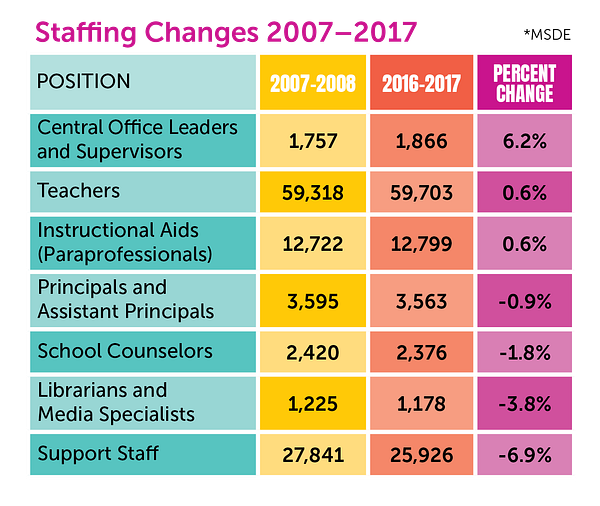

The unavoidable fact is that since the Great Recession, education spending in Maryland just stalled out. The historic increase in funding of the 2002 Bridge to Excellence Act brought with it increases in staffing. By adding nearly 3,960 teachers from 2003 through 2007, Maryland schools drove down their 15.7 students-per-teacher ratio to 14.3. Schools also added 2,200 instructional aids and 2,125 support staff in those five years. With those increases came Maryland’s #1 spots in Education Week’s state rankings (2009–2013) and in Advanced Placement performance rankings (2006–2016).

But following that improvement through 2007 came a decade of mostly flat funding, a students-to-teacher ratio that’s risen to 14.8, and decreases in the staffing levels of school counselors, librarians and media specialists, and sup-port staff (see the chart below). At the same time, since 2007, Maryland has added 40,500 more students. This strain has had a clear impact on student achievement: Maryland has now dropped to #5 in Education Week’s rankings, fallen in AP performance rankings, and is mired in the mid-20s in NAEP scores.

The vital importance of adequate staffing surely comes as no surprise to educators, but it hit home with the Kirwan Commission, the group studying top-ranking school systems and education policy and developing recommendations for Maryland’s next generation school funding formula. Recognizing the effect of deteriorating staffing levels in teaching — and increasing enrollment and student needs — the Commission’s preliminary recommendations include an “ample supply of high quality competitively compensated and diverse teachers and school leaders.” Also on the commission’s radar is providing the important wrap-around services and mental health staffing in schools that serve high-poverty communities. That means more counselors, more support staff, and more community schools.

The Kirwan Commission’s researchers — the ones who found that Maryland schools are $2.9 billion underfunded — were specific about the areas identified as needing more resources. They are all staffing-related: small class sizes; art, music, PE, world languages, technology, CTE, and advanced courses; significant time for teacher planning, collaboration, and embedded professional development; additional instructional staff, including instructional coaches and librarian/media specialists; and a high level of student supports from more counselors, nurses, behavior specialists, and social workers.

Efforts are underway to create a lockbox for revenues and ensure it goes to schools.mseanewsfeed.com

Of course, schools wouldn’t run effectively and high quality instruction wouldn’t be possible without the incredible work that support staff do every day. MSEA is arguing forcefully to the Commission that in most schools, we need many, many more of these professionals in order to meet the needs of students.

Relationships matter. After years of understaffing — years of students having fewer and fewer interactions with educators in school — it has finally culminated in an adverse effect on student learning. Maryland educators have been warning the public about this for years. We must turn these numbers around.

SOLVING THE PAY PROBLEM

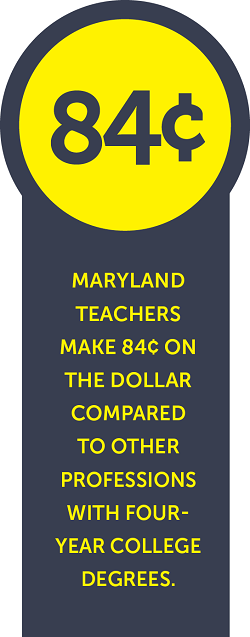

Every community wants a great public school, one in which skilled professionals provide the creative and challenging learning environment students deserve. But skilled professionals come with a cost. In 2015, the “teacher pay penalty,” the gap between educators’ pay and that relative to other professionals with comparable levels of education and skills, was 16 cents on the dollar, according to the Economic Policy Institute. In other words, educators received 16% less in pay than their peers in other professions.

Similar to the staffing issue, Maryland made great strides following the implementation of the Thornton funding formula in the mid-2000s — raising the average teacher salary by 25% between 2003 and 2008 — only to lose that improvement in the aftermath of the Great Recession. That’s led to high levels of teacher turnover and challenges recruiting enough teachers. Last year, the State Board of Education projected a shortage in certificated teachers in every school system in Maryland.

Like the overwhelming staffing issue that often drives educators to other professions, the Kirwan Commission is addressing the teacher pay issue with some positive recommendations that could boost career opportunities for current and future teachers.

The Commission moved forward on a recommendation to raise Maryland’s average teacher salary to the equivalent of New Jersey’s and Massachusetts’ average teacher salary within the first four or five years of the Kirwan plan’s implementation.

If teacher salaries grow in those states at the same rate they have for the last 15 years — a conservative estimate considering the recession that took place during that time — Maryland’s average teacher salary (including other certificated staff on the same salary schedules) would need to reach approximately $90,000 to catch up to their pace.

If teacher salaries grow in New Jersey and Massachusetts at the same rate they have for the last 15 years, Maryland’s average teacher salary (including other certificated staff on the same salary schedules) would need to reach approximately $90,000 to catch up to their pace.

That’s a 32% increase from where Maryland teachers are now (average teacher salary was $68,357 in the 2016–17 school year). And that’s just the first step in closing the pay gap between teachers and other highly-skilled professionals, like architects and accountants.

“Those Things You Learn Without Joy You Will Forget Easily.”mseanewsfeed.com

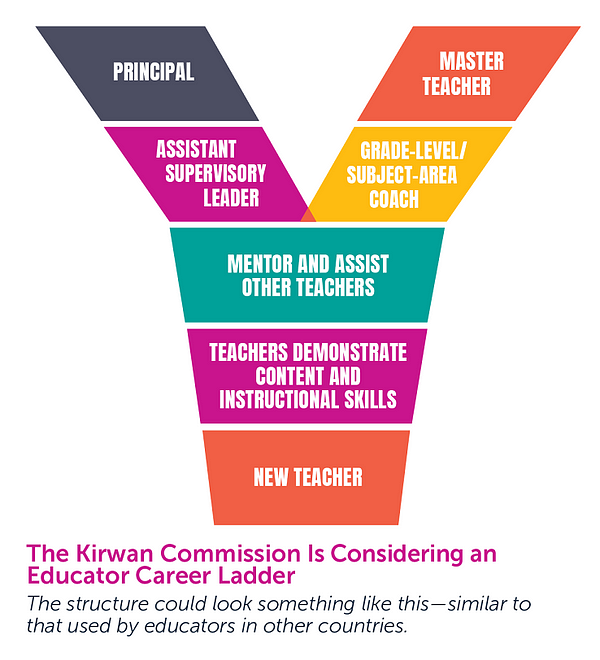

While the Commission is working towards a goal of having every teacher matched against their counterparts in other professions, its members want teacher leaders to gain additional compensation as they move up “career ladders,” similar to Singapore’s model (see a sample career ladder below). As teachers excel and gain more expertise and take on more responsibilities they move up the ladder to become, for example, instructional coaches, department chairs, and eventually master teachers.

The Commission wants to develop a statewide Y-shaped framework where exemplar teachers have a choice between rising up a teacher branch or an administrative branch — with the tops of both paths making the same high salary. Outside of some broad parameters, the exact details of the career ladders and salary structures would remain subject to collective bargaining in each of Maryland’s 24 school districts.

Despite its progress on salary and staffing issues, the Commission has not yet seriously addressed how we can support non-certificated staff in their work for students. There’s no other way to put it: it’s disappointing. MSEA will continue to push the Commission to adopt our ESP proposals to pass a state law guaranteeing that every single person who works in Maryland public schools receives a living wage for their work and to significantly expand the number of para-educators who work in our schools — especially to support students in elementary school grades and students in special education.

MSEA will continue to push the Commission to adopt our ESP proposals to pass a state law guaranteeing that every single person who works in Maryland public schools receives a living wage.

With the potential of the Kirwan Commission recommendations offering a sea-change in how we view education in Maryland, real progress, and real hope, is once again within reach. We’ll need every educator on board to make it happen.