The School Discipline Crisis

You can’t talk about student discipline and behavior today without discussing the complex reasons for it.

Systemic poverty, institutional racism, mass incarceration, school funding and supports, technology, class sizes, under-resourced communities, lack of fresh air and exercise, student access to drugs, the opioid crisis — all these things and more help to create the difficult classroom environments so many of our students and educators are experiencing today.

But the overwhelming questions of who is accountable and who provides the compassion, resources, and time to tackle these issues are just beginning to be addressed.

This tremendous responsibility has fallen almost exclusively on schools and educators. We have more sustained time with children than anyone else. In the absence of comprehensive supports within students’ own communities, it has indeed become one of our most pressing professional issues.

“Our job and passion as educators is to educate the students in our care,” says MSEA President Cheryl Bost. “That seems like a simple mission, but it’s complicated by numerous mandates, revolving curriculum guides, increased data collection, cumbersome evaluations, increased class sizes and caseloads, and a multitude of other distractions.

“Combine those demands with students coming to our schools with increased exposure to trauma, increased poverty, increased homelessness, fewer opportunities to socialize, and a decrease in social services and counseling opportunities,” Bost added, “and it’s no surprise educators and students are feeling the pinch, which feels more like a tightening vise for many across the state.”

There’s a vacuum that exists in many school districts, where there is little to no guidance and even less consistent follow through. While the Maryland State Department of Education’s (MSDE) 2014 guidelines required each school district to have a code of conduct that was to be rehabilitative, keep more students in school, encourage discretion as opposed to automatic responses to behavior, and require an explanation for the use of out-of-school suspensions, the implementation at the local level has never been consistent nor has it improved many outcomes.

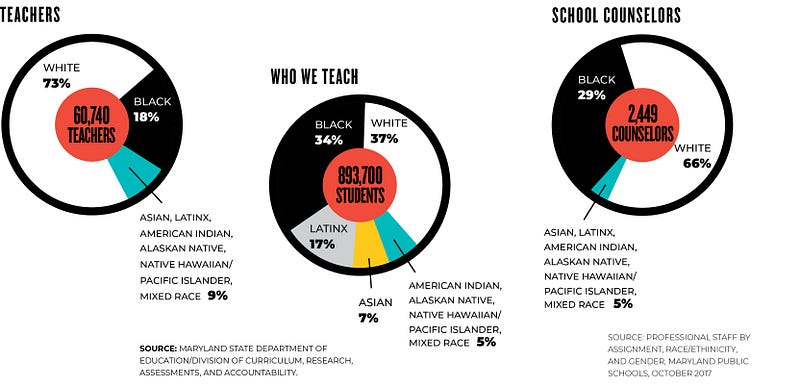

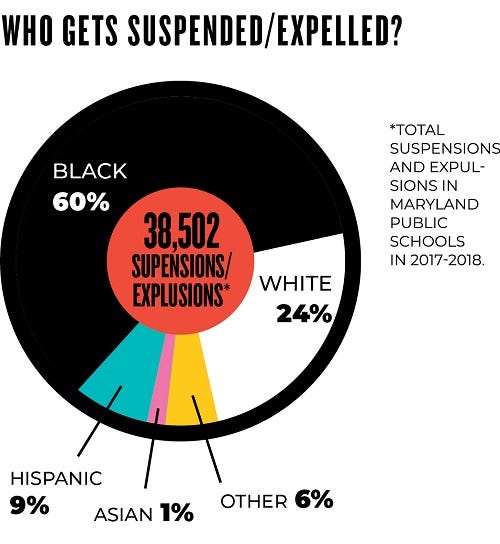

In its December 2018 report, the Maryland Commission on the School-to-Prison Pipeline and Restorative Practices acknowledged what many educators already knew: MSDE’s guidance to local schools about how to apply its guidelines resulted in little change in suspension rates or improvement in the well-documented racial disparities in discipline practices.

“While the demands on us are weighty, there are numerous studies and personal experiences that prove that we, as members of the education profession, must take a look in the mirror,” Bost said, “and be frank about examining, owning, and moving to correct implicit biases, institutional racism, adultism, gender inequities, and cultural stereotypes, whether race-, ethnic-, wealth-, or gender-based.

“Our job is not only to impart content standards. We simply can’t pretend that we have a job to do whether that is to deliver math content, drive a bus, clean the school, develop artists, or register students for classes without first acknowledging that above all, our job is to educate and guide students in our care to become productive citizens.”

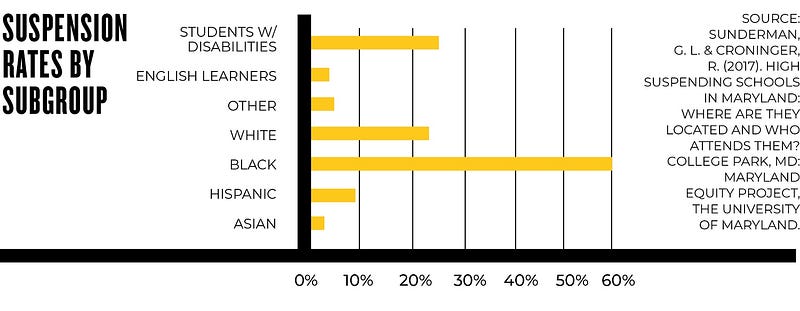

Accepting this charge requires a serious look at the discipline and suspension statistics that show an undeniable bias against young people of color and students with disabilities. Some of it is because of the way adults react to the same infraction.

Bias plays a huge role in the treatment and discipline of Black girlsmseanewsfeed.com

In its 2018 report High Suspending Schools: Where Are They Located and Who Attends Them?, the University of Maryland’s Maryland Equity Project wrote: “The high rate of variability across schools — and districts — suggests that the use of disciplinary consequences is related to contextual variables that go beyond individual student behavior. Indeed, it appears that both the district and the school that a student attends play a role in suspension rates. We did not find that high suspending schools are located in any one district or region of the state. Rather, they are found in both rural and urban areas, in small and large districts, and in all regions of the state. This suggests that districts with large numbers of high suspending schools either have a culture where exclusionary discipline is condoned or are not providing the leadership, resources and training staff need to prevent inappropriate behavior. The variability in suspensions across schools provides evidence that schools can do things differently, but some may need more support than they are currently receiving.”

Educators can play critical roles in breaking down biases at all levels.mseanewsfeed.com

Bias is an unavoidable truth in this scenario and through MSEA’s racial justice programming and our bias assessment tool, available through our partnership with First Book, we are committed to progress. Other important, relevant resources free to MSEA members can be found at First Book, including cultural competency and social-emotional resources for students of all ages.

Take a deep breath. It will get personal. That’s okay.mseanewsfeed.com

Understanding and Acceptance

In Maryland, 60% of adults reported adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the 2015 Maryland Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the nationwide data-gathering survey (of non-institutionalized adults). ACEs is a scorecard of events of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction that happen to a child under the age of 18.

That statistic means that every classroom has children who have had, or are experiencing, trauma. “Just because you haven’t been told a particular child’s story doesn’t mean they don’t have a story,” says Donna Christy, a school psychologist in Prince George’s County.

Almost half the nation’s children have experienced at least one or more types of serious childhood trauma, according to…acestoohigh.com

ACEs include physical, sexual, and verbal abuse, physical and emotional neglect, a parent who’s an alcoholic, drug addict, or diagnosed with a mental illness, having a mother who experiences abuse, losing a parent to abandonment or divorce, and having a family member in jail. These manifest as so many of the behavioral issues we see acted out at school.

“Kids weren’t born wanting to be difficult. A child acts out because they don’t have the words to express what they are experiencing and feeling,” Christy says. “Their behavior is saying: I’m frustrated, I’m confused, I don’t understand what’s going on, I’m scared. If we can just sit down with them to find out what the problem is, we can help solve it to the point that they can function in class. We can teach them a more adaptive way to solve their problems, and have their needs addressed.”

“Sixty minutes of daily unstructured free play is essential to children’s physical and mental health.” — The American…mseanewsfeed.com

This doesn’t excuse bad behavior or nullify consequences, but works to understand and teach students a better way to communicate and resolve problems.

Policy? What Policy?

Many districts are in a crisis mode themselves when it comes to school discipline policies. Restorative practices is almost universally considered the most promising program and at the forefront of any reform effort. However, many school districts are dragging their feet on making a commitment to effective implementation and this exacerbates the problem for educators and students.

New Toolkit & Infographic: What Are Restorative Practices? An Educator’s Guide to Fostering Positive School…schottfoundation.org

In Baltimore County, where the Teachers Association of Baltimore County (TABCO) has created a Discipline Action Workgroup, co-chairs Sonja Floyd and Tammy Mills say that the vacuum of clear policy adds to the problem, and that students are falling into the vacuum: “Students who could be swayed by meaningful intervention are seeing no benefit or incentive to make the tough choices in difficult situations.” As they study the issue and push their board of education — so far disappointingly — to take action, they have become the experts the county needs to move forward.

“TABCO and the board agree that every school needs a discipline plan per our master agreement,” Floyd and Mills say. “However, the board isn’t interested at this time in holding principals or schools accountable for having this plan in place.”

In March 2019, Dorchester Educators (DE) organized at a board of education meeting where more than 25 educators shared examples of the magnitude of the school discipline problem in the mostly rural county. They’ve received no reply. But DE President Katie Holbrook sees an opportunity. Starting July 1, a new interim superintendent takes over. He’s 30-year Dorchester County educator and principal (and union member) David Bromwell, who lists discipline and safety among his top issues.

“We’re committed to our students. Respect starts at home — for authority and for education,” says Holbrook. “But we have to play a role in it somewhere. At the same time, our hands are tied by this lack of policy and it becomes very challenging.”

This lack of predictable, meaningful policy does a disservice to students, says Robin McNair, restorative practices program coordinator for Prince George’s County Public Schools and a member of the Maryland Commission on School-to-Prison Pipeline and Restorative Practices. “It harms the process which plays out as a lack of safety and respect for both the educator and student, frustration for both, and a lack of faith and trust in administration.”

Ninth grade U.S. history teacher Robin McNair is a believer in restorative practices. “Just one suspension doubles a…mseanewsfeed.com

In the absence of policy, educator frustration is very high.“We have to examine where our frustration comes from,” McNair says. “Is it from how we relate to, or view, the student? Have we examined our bias? Do we have high standards that are unrealistic for certain students? Am I responding to students in a way that is respectful and honorable, making sure the student’s dignity remains intact? Have we established practices about how to be with one another in the classroom?”

There’s also growing hope. With the help of a $500,000 grant from NEA, the Howard County Education Association (HCEA) is playing a big role in firmly embedding a policy of restorative practices in its schools by providing comprehensive training to educators, community members, and administrators.

“The relationships built in classrooms through this grant will help to identify and connect children to counselors, social workers, and other services to support their needs,” said HCEA President Colleen Morris. “Every child needs an educator that can provide them social and emotional support — someone they can confide in and trust to guide them both personally and academically.”

What’s clear is that’s there’s no singular quick and easy solution for this complicated, frustrating issue. Educators, MSEA, and local associations will continue to push for comprehensive, educator-informed solutions to realistically address this crisis over the long-term — and ensure that school is a safer place for all students and school employees.

See related stories: Black Girls and Discipline, What’s Adultism Anyway? and The Power of Play.