Resisting Educational Racism: Minority Students in Montgomery County Organize Agaisnt Bias

Minority Students in Montgomery County Organize Against Bias

Cultural capital. It’s what we bring to the table every time we are present. Every interaction with another, a class, a meeting, a social encounter—the act of simply being seen and heard displays elements of our cultural capital. It can be the color of our skin, the clothes we wear, our accent, our education, our mannerisms. Cultural capital is perceived in comparison to others and is, historically, a key means by which social mobility is consciously or unconsciously granted or withheld.

So it follows that in a society historically dedicated to sustaining and increasing the status and power of white people, students of color who come to the table with cultural capital that is different have not been perceived by the dominant culture as deserving the same opportunities as white students because their cultural capital does not feed or support the system in the same way. MSP brings students together to own their rich and deep cultural capital—their individual assets and those of their communities—and move forward with confidence and pride, knowing they are heard, seen, and supported.

Deconstructing embedded institutional racism is at the heart of the anti-racist work taking place in many homes, schools, places of worship, communities, and businesses around the country. But in Montgomery County high schools, the work started long before the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so many others thrust this work into the national conversation.

The Minority Scholars Program was founded at Walter Johnson High School in Montgomery County in 2005 after the school was offered a full scholarship from Morehouse College for a Black male student who met the minimum requirement of a 3.0 GPA. The school was unable to find a student to take advantage of the offer.

Concerned administrators asked Mike Williams and Esther Adams, two of the school’s five Black teachers at the time, to build a program to close the opportunity gap, which, Williams said, “was staring us in the face.”

The opportunity gap is also what drives the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future. The expansion of pre-k and community schools, earlier interventions for struggling learners, more funding for special education, and more options for high school students to claim and pursue career and technical education can’t erase the implicit and explicit biases and institutional roadblocks students of color face in school.

“Creating change is hard. It’s no small task to figure out where to start,” said Nico Ballón, an MSP alum of Walter Johnson HS who at 22 has completed his master’s degree and is working on Capitol Hill as a press aide. “MSP found a way. They have created a blueprint to help minority students succeed both inside and outside of school.”

MSP’s mission is to close the opportunity gap that exists for Black and Brown students through the Five Keys of MSP—student-centered, student-led, and student-empowering areas that include: academic achievement; student voice; leadership development; enhancing cultural capital and sense of belonging; and community engagement. For many minority students it is deeply affirming, if not revelatory, to discover that they are not alone in their hurt and aspirations, that the MSP movement is larger than any one of them alone, and that there are adults who care and can help them gain control of their education.

“In MSP, students have a seat at the table. Students have an important role to play in developing creative solutions to address the opportunity gap and in influencing their peers to be better scholars. Sharing their stories and their experiences with educators not only empowers students but transforms educators,” said Deb Delavan, the MSP sponsor at James Hubert Blake High School.

“When I joined,” said Nico, “I immediately felt the drive and passion of the students. The staff of MSP pointed to light and injustice and challenged us to stand up to it. They didn’t tell us how. They told us they believed in us to figure it out. As students we had never been given that confidence or liberty before.”

Overcoming Bias

It seems really strange to be in a place of education and learning and no one wants to actually learn from one another,” said James Hubert Blake High School student Jonathan Myers. It’s not surprising, then, that he feels the most important skill he’s learned in MSP is “the delicate balance of being transparent and diplomatic. Sometimes when we bring up the topic of equity, many find it uncomfortable or too controversial. We as advocates must learn when to push and when to pull back for the comfort of others.”

MSP students find such nuance, inspiration, courage, and support to confront bias through the Five Keys and its goal-setting framework of action, which includes: improving GPAs; getting themselves and others into AP and honors classes; peer-to-peer tutoring; gaining access to college visits and support in the application process; securing student government positions; leading peer and teacher trainings; learning leadership skills like agenda and calendar setting, organizing, and public speaking; recognizing and honoring ethnic and racial identity; and serving as community role models and ambassadors. These skills create access for MSP students. But, despite the program’s expansion and progress in the 16 years since its founding, students still too often hit a brick wall.

“The most significant barrier I’ve faced was that I was told to stay away from higher level classes going into high school. That severely hindered my potential as a freshman and my preparation for standardized tests,” said Jonathan. “My parent couldn’t afford tutoring and my scores failed to reflect my qualities as a student. These barriers stemmed from racial bias and being unable to afford the resources that the white middle class receives most of.” This year, Jonathan has been nominated for the full-tuition Posse Scholarship for his academic and leadership success.

Like Jonathan, Jade Shaibani, a student at Walt Whitman High School, feels the sting of unchecked biases at school. “I found it strange when my school administration wanted students to facilitate a workshop on microaggressions after a racist incident, but left it up to white students to facilitate a topic that they had no experience in.”

Racist situations like these are encountered by students of color every day; MSP provides a safe place for them to share their pain and frustration in a community that affirms and supports. Emboldened by the skills they are learning, these students learn to respond to racism with maturity and reason. “I have definitely been able to have candid conversations about race with my peers since I joined MSP,” Jade said. “It has become easier to pose issues like race as a discussion, instead of an argument. I’m educated on racial inequality in our school system and I am always open to discussing this issue with others.”

A Sound Structure

Each of the 25 high school and 23 middle school MSP programs, supported by a school sponsor, determine how it will go about achieving the foundational Five Keys of MSP. At the high school level, says co-founder Mike Williams, each school chapter sends several members to a monthly county-wide MSP task force meeting. “Leaders from each school share and discuss challenges, best practices, and how to implement our initiatives. One of the main task force jobs is to plan the MSP Retreat. Our last in-person retreat saw just short of 900 students from across the county attend.”

Also integral to the program and the students’ depth of understanding the opportunity gap and equity is its six-week summer internship program attended by one student chosen from each high school through an application process, a testimony to its popularity and success with student leaders. The interns spend six weeks going deeper into the Five Keys of MSP by learning more about the opportunity gap, race and equity in education, leadership, and community organizing. They share their stories, analyze issues of systemic racism, develop leadership and public speaking skills, and create community among themselves.

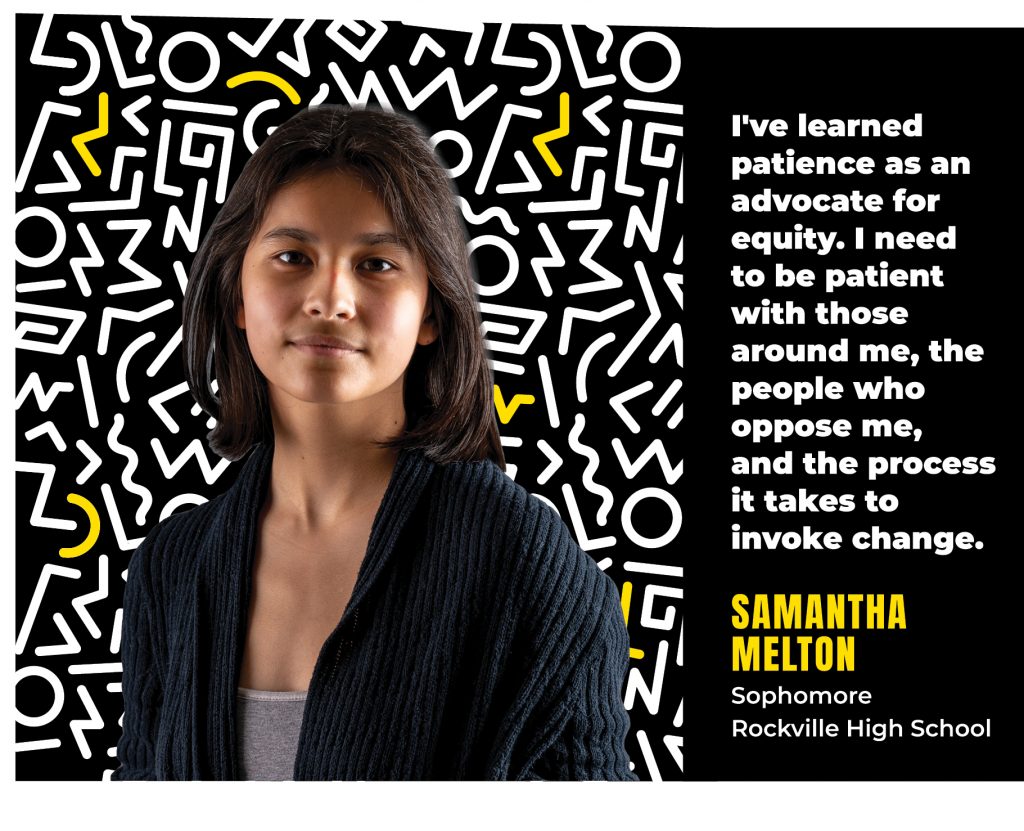

“At the end of the summer they facilitate a workshop for Montgomery County Public School staff on race, equity, student voice, and the opportunity gap,” said Williams. “They essentially become the leaders of the leaders and the spokespeople for MSP across the county and state. Many will lead workshops at their own school, help train their peers, speak at county- and state-wide events, and facilitate various work-shops for adult educators.” Christine, Ila, Jade, Jonathan, Micah, Samantha, and Udy, the students featured in this article, are all graduates of the 2021 internship program.

Creating More Opportunities

“When we say the MSP movement is student-led and student-driven, we mean it. I think our framework of action is one of the most beautiful things about MSP and appreciate the sponsors who also ensure this model upholds as part of our advocacy efforts in Montgomery County and across the nation,” said Maria Salmeron Melendez, an alum who is currently studying education policy and analysis at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Building on the Montgomery County Education Association’s long-running commitment to MSP, MSEA, with the help of NEA Community Advocacy and Partnership Engagement Grants, is supporting and expanding the MSP program in Montgomery County and across the state to fund the start-up of more MSPs in more schools and provide the important professional development MSP sponsors need to support the programs. Networking and sharing among the MSP community is one of its strengths, says Maria: “It always struck me how we all tackled the gap in our schools. Whenever we came together, we would realize the complexity of it and get even more frustrated—yet more empowered—to lead with our hearts and advocate for educational equity.”

“MSP has changed my life for the better,” said Udy Mbanaso of Richard Montgomery High School. “If I hadn’t joined MSP freshman year, I would not have participated in the summer internship, which was truly the highlight of my summer. Being able to work with 25 different students from 25 different high schools, and then planning a workshop for teachers and staff, meeting with the superintendent, and just making a difference, was such an amazing experience. MSP has also brought the community closer— at the internship, we were connecting all parts of the county, to make a change as a group, and then individually at our schools.”

Learn more about the Minority Scholars Program

The Minority Scholars Program is a student led, student based, and student driven program, aimed at closing the opportunity gap. The program has five key aims:

• Improving academic achievement

• Raising student voice

• Developing leaders

• Developing leaders

• Enhancing cultural capital and sense of belonging

• Reaching out to our community

Initiatives employed throughout members school programs include: community outreach, peer to peer tutoring/mentoring programs, college visits, and a speaker series. For more information about MSP or starting a program in you school, contact [email protected].