Nurturing Resilience — Post-Traumatic Growth

Educators can help students move away from their trauma towards growth, resilience, success, and happiness.

“So many educators are already using trauma-informed practices and don‘t know it. It’s the nature of educators to be nurturing and accessible, but the real win for students is when we have schools that are consistently responding to students with trauma–sensitive classrooms, embedded restorative practices, and high-quality social-emotional learning resources.” — Prince George’s County School Psychologist Robert Hull

The idea of post-traumatic growth — gains in compassion, openness, and empathy — has been around since 1995, when researchers found that in the trauma of losing a child, bereaved couples somehow reported consistently positive personal change in the years after their loss. Since then, it’s been applied to the effects of war on veterans, a cancer diagnosis, and terror attacks.

Studies show that certain powerful personality traits lend a helping hand. But these traits — optimism, extroversion, and openness to new experiences — aren’t at all what educators see when students arrive in their classroom suffering from trauma in their homes and communities. Not everyone experiences post-traumatic growth, of course.

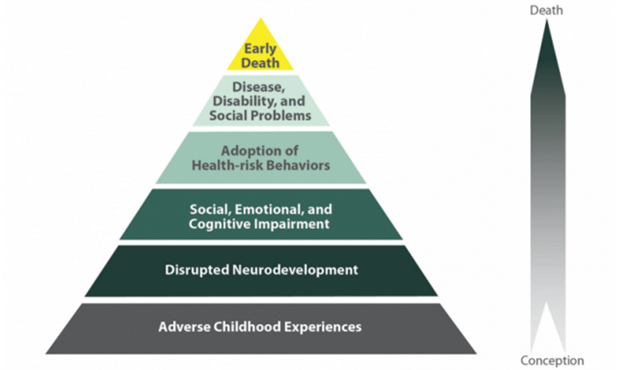

What educators see are stunned, angry, lonely, hungry, depressed, neglected, and exhausted children — struggling for recognition, acceptance, understanding, and patience. They are frightened and burdened — and their numbers are growing. “Adverse childhood experiences,” said Dr. Robert Block, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, “are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today.” Where “the resilience of youth” was once assumed to be a given, experts are recognizing more and more the impact of childhood trauma.

Trauma-Sensitive Schools and Safe and Supportive Schools benefit all children. TLPI embraces a whole-school approach…traumasensitiveschools.org

Christopher Layne of the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress says that the outcomes for students experiencing trauma range from deterioration of functioning to post-traumatic growth, with many students maintaining themselves in the “stable but maladaptive outcome.”

These students are on high alert for perceived threats and are in a constant state of mobilizing for a fight, flight, or freeze response as they wait for the next betrayal. That makes it hard to concentrate, remember, and learn. It doesn’t matter if the threat is not there — perception is everything to these students and their responses are often beyond their conscious awareness.

“Children are especially sensitive to repeated stress activation because their brains and bodies are just developing,” said Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician in San Francisco whose Center for Youth Wellness prevents, screens, and heals the impacts of adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress.

“High doses of adversity not only affect brain structure and function, they affect the developing immune and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed.” It is an emotional and physical response to their environment.

This background is helpful, but educators don’t need another degree to help these students learn, says Robert Hull, a Prince George’s County school psychologist and editor, with Eric Rossen, of Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals.“So many educators are already using trauma-informed practices and don‘t know it,” Hull said. “It’s the nature of educators to be nurturing and accessible, but the real win for students is when we have schools that are consistently responding to students with trauma–sensitive classrooms, embedded restorative practices, and high-quality social-emotional learning resources.”

What educators and schools do need are training and programs that support post-traumatic growth by recognizing trauma and focusing on removing the barriers to students in the classroom.

“Our job,” Hull says, “is to help children, who lack the resources and mobility of adults, realize that with the support of their school community, they can move away from trauma and towards growth and resilience — even happiness. That’s post-traumatic growth.”

If you know anything about New Orleans public schools, you probably know this: Hurricane Katrina wiped them out and…www.npr.org

The 10 Principles of a Compassionate School

- Focus on culture and climate in the school and community.

- Train and support all staff regarding trauma and learning.

- Encourage and sustain open and regular communication for all.

- Develop a strengths based approach in working with students and peers.

- Ensure discipline policies are both compassionate and effective (Restorative practices).

- Weave compassionate strategies into school improvement planning.

- Provide tiered support for all students based on what they need.

- Create flexible accommodations for diverse learners.

- Provide access, voice, and ownership for staff, students and community.

- Use data to: identify vulnerable students, and determine outcomes and strategies for continuous quality improvement.

Identifying Trauma

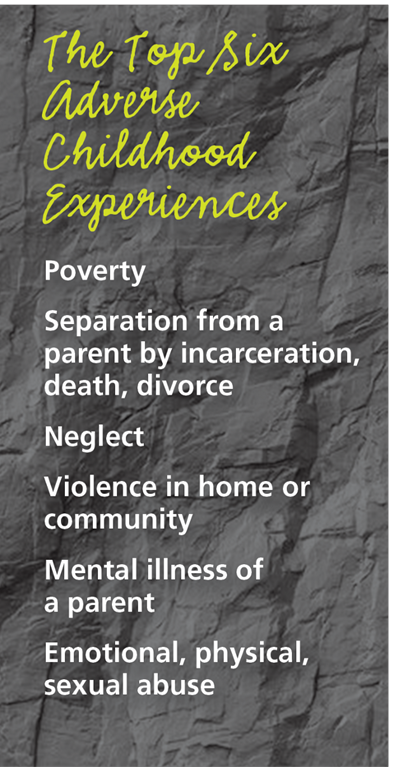

Abuse, neglect, and traumatic experiences are called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). In study after study, a high number of ACEs are linked to poor health and well-being. Since those studies, determining ACEs has become the standard for assessing the quality of a childhood.

In many states, the recognition of the impact of ACEs is well-established. Illinois requires social and emotional screenings for children as part of their school entry examinations; Massachusetts’ Safe and Supportive Schools provides a statewide framework and grants for trauma-sensitive schools; the Trauma-Informed Schools Initiative in Missouri requires the departments of mental health, social services, and education to collaborate and provide training to all school districts; and in Washington State, the Compassionate Schools Initiative is a collaboration of the public schools, a university, and mental health agencies.

School psychologist Robert Hull has been advocating for trauma–informed practices for years. Seven years ago, his University of Missouri graduate level class, Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students, became the basis for a three-credit MSDE certified professional development course in Prince George’s County that’s now offered three times a year. “We recently trained the ESOL leadership staff to teach it a a way to respond to the multiple adversities that so many of our ESOL students experience,” Hull says.

Ann Hammond, the Frederick County Public Schools supervisor of psychological services, used Hull’s book in developing her own three-credit professional development course. Hammond says system-wide interest on the effects of trauma is growing; she’ll be presenting on ACEs to the board of education, to all district principals, and to teams from every school in October.

Shifting the Conversation

Poverty and its consequences are the number one cause of ACEs in Maryland, and the biggest impediment to student learning. And while the policy conversation in Maryland is beginning to come into focus on more child-centered and appropriate approaches, there are real opportunities to make further progress.

Nearly 43 percent of children living in low to middle income communities around the world will not reach their…www.baltimoresun.com

In 2014, MSDE banned the controversial zero tolerance policy — which easily suspended or expelled troubled students — and consequently opened the door to a broader conversation on the discipline question. Since then, trauma-sensitive schools, social-emotional learning curricula, and restorative practices have shifted a once one-size-fits all punitive culture to one where what’s behind the child’s behavior becomes the focal point of educators, school psychologists, and administrators.

Yet for that culture to really take root and comprehensively help students experiencing trauma, it takes more than rewriting policy — it takes adequate funding for programs, staff, and training.

As the Kirwan Commission prepares its recommendations for a new funding formula, MSEA will be pushing for solutions that comprehensively address student poverty and its consequences, whether through improving the funding formula to better support students in poverty or through specific, research-backed programs supported by educators.

Bob Hull testified before the commission in August asking it to recognize and fund trauma-informed education, which includes community schools where underserved families experiencing the traumas of poverty, dislocation, and crime can gather for education, social and health services, and recreation. He’ll be working this year with other MSEA members to build a trauma-informed education coalition that will focus on providing students with trauma-sensitive schools.

The urgency of developing trauma-sensitive policies and programs has never been greater. MSEA and its members are leading the way in pushing for trauma-informed practices to be embedded through policies, regulations, and laws.