Maryland Is 49th in Teacher Autonomy

That’s a huge problem.

That’s a huge problem.

Classroom autonomy for teachers. According to research, it’s correlated with job satisfaction and retention. Unfortunately, in a recent report by the Learning Policy Institute, Maryland was ranked second-lowest in the country — ahead of only Florida — in teacher autonomy, defined as control in selecting textbooks and class materials; evaluating and grading students; selecting the content, topics, and skills to be taught; disciplining students; selecting teaching techniques; and determining homework amounts.

The finding is based on data from the School and Staffing Survey, a poll of more than 37,000 teachers conducted by the federal National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Digging deeper into the report reveals interesting discrepancies on autonomy across time, teachers, and schools.

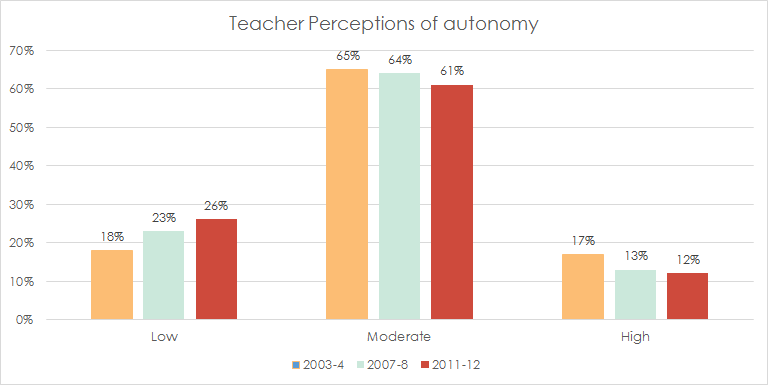

The NCES report compared three years of findings on autonomy: 2003–4, 2007–8, and 2011–12. Although a majority of teachers felt they had “moderate” autonomy, teacher perceptions of their autonomy slid each time the survey was given.

Who has more or less autonomy?

While autonomy needs to be balanced with levels of consistency across classrooms, the diminishment of autonomy can have a real impact on job satisfaction and the likelihood of educators to remain in the profession. Low levels of autonomy often appear to be most acute among teachers, schools, and subject areas where retention numbers are the worst.

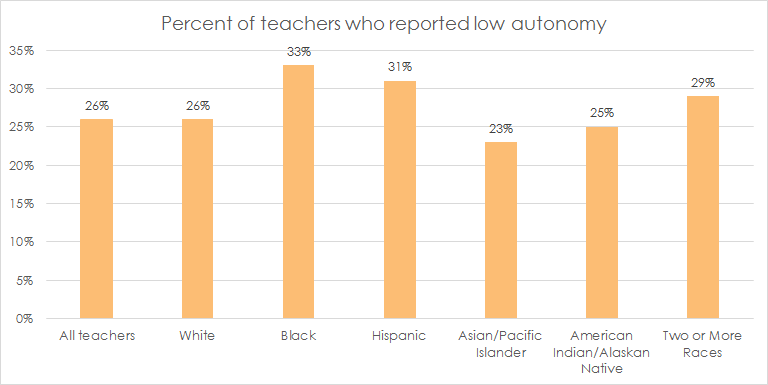

NCES found that in the 2011–12 version of the survey, 26% of teachers reported having “low” autonomy, with larger proportions of African-American and Hispanic teachers reporting low autonomy. Elementary school teachers were much more likely to report low autonomy than secondary teachers by a 12 point margin of 31% to 19%.

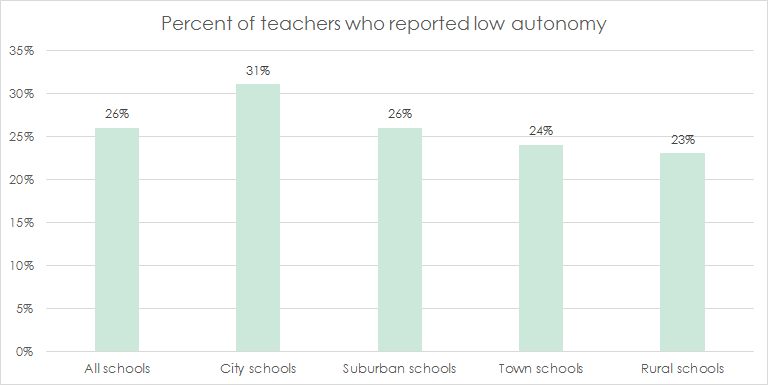

Community density also appeared to be correlated with reports of low autonomy, with teachers in rural schools reporting the most autonomy and teachers in urban schools the least.

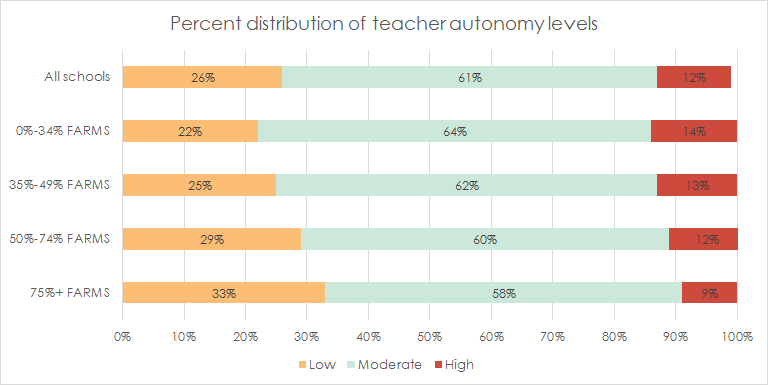

The socioeconomic status of a school’s students also tracks with teacher autonomy. The NCES report found that higher levels of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch equated with lower levels of teacher autonomy.

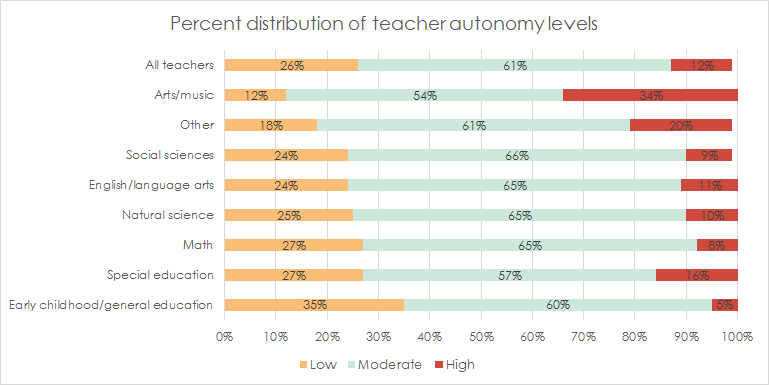

Finally, different types of teachers report quite different levels of autonomy. Looking for high levels of autonomy? Visit an art or music teacher’s classroom. Head to an early childhood or general education classroom for the lowest levels of autonomy.

Now what?

Ensuring that educators can make expert judgements based on their professional expertise is a key factor in improving the working conditions of educators — and by extension the learning conditions of students.

Finnish educator and researcher Pasi Sahlberg has written that “perhaps the most powerful lesson the US can learn from better-performing education systems [is] teachers need greater collective professional autonomy and more support to work with one another. In other words, more freedom from bureaucracy, but less from one another.”

In Maryland, nearly half of new teachers will leave the profession by the end of their third year.mseanewsfeed.com

From giving new educators additional time to co-plan, observe veteran educators, and work with their mentors — as envisioned in a pilot program in Senator Paul Pinsky’s (D-Prince George’s) Teacher Induction, Retention and Advancement Act of 2016 — or in innovative ideas like teacher-led schools, worthy ideas are out there. It’s up to us to get them implemented and make sure that educators can exert their professionalism and autonomy to make educational decisions that will best benefit their students.