Insufficient Funds

How the budget shortfall directly affects our work as educators and our students

From Time Magazine to the New York Times, from Arizona to North Carolina (and Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia in between), the situation and status of public school educators is getting plenty of press and increased recognition. This comes after protests, work stoppages, and reports of educators leaving states where student resources are grossly outdated, schools are resorting to four-day weeks, and school employees can’t pay their bills.

Here in Maryland, educators are fighting for their right to a well-respected profession — a profession celebrated in other countries with high regard and compensation, status and pride. Too many educators are struggling to stay in the jobs they love, nurturing and molding students to be the leaders we need in an increasingly complicated and fast-paced world.

There’s no doubt that many of the issues educators and schools face can be addressed through better funding that makes it possible to meet the expectations of academic success with 21st century resources and educators who are treated and respected as professionals.

Yes, we have a critical opportunity on November 6 to pass Question 1, the constitutional amendment to make sure casino revenues go to increasing support for public schools but our promise to students and communities must be bigger than that. The candidates elected this November will rewrite the all-new school funding formula that the General Assembly will begin to debate in January. It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create an improved formula that makes a new Maryland Promise to educators, students, and communities. It’s a promise MSEA is fighting hard to realize.

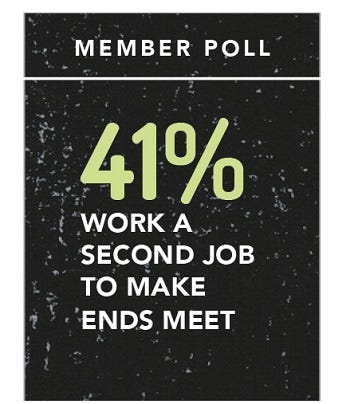

MSEA’s recent poll of 800 members exposed the degree to which Maryland educators struggle — but as you’ll read on these pages, not one of them would leave their job.

“I know that what I do every day helps children learn, grow, and become a strong and caring part of our world,” said Cecil County paraeducator Debbi Norton-Russell. “To help a child learn is to open their mind and imagination to a whole new world of adventure, where their creative spirits can soar to the stars and beyond.”

That is the heart of an educator.

Cecil County paraprofessional Debbi Norton-Russell is a single parent who has been working for the school system for 12 years. “I started working as a paraeducator because I needed a full-time job with hours that would allow me to care for my son when he was small. The struggles that I have had to overcome to make ends meet are difficult and physically and mentally exhausting.”

For years, Debbi has worked more than her full-time hours as a para — she’s done taxes, bought and sold items on Craigslist, and more than once made the choice between her own medication and food on the table. Right now she has a room for rent on Airbnb and is looking at a bartending gig.

“It’s really hard raising a child completely by yourself, but it’s even harder when your paycheck barely covers your health insurance, dental, and vision costs. My paycheck barely covers my mortgage, let alone the electric, telephone, food, gas, and car insurance bills.

It saddens me that I work with such precious children and have such a difficult job trying to educate kids to be all that they can be, yetmy salary is below poverty wages.”

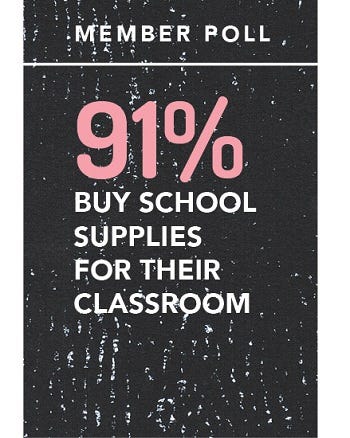

Our recent member poll told us that 91% of Maryland educators pay for school supplies out of their own pockets. And perhaps nowhere is that harder felt than by early career educators like Alexandria Anderson, Anne Arundel County, and Chelsey Herrig–Paine, Charles County, both in their second year of teaching elementary grades.

Alexandria and Chelsey have already spent $1,300 between them this year for supplies ranging from bins and flash cards to dry erase markers and large sticky pads. They both sacrifice to be sure their students have what they need while struggling with student loans, rent, and planning for the future.

“I’m just now starting to pay back my loans which is going to take a chunk out of my pay,” said Alexandria, who is also a hostess at a café in College Park. “That, on top of purchasing supplies — sometimes weekly depending on the needs of my students — and my other personal financial responsibilities coming out of my salary, means that some weeks I barely have enough to cover everything.”

“I could easily spend my entire paycheck on school supplies,” said Chelsey, who was given $100 to start her classroom this year. “Sometimes I swap out a luxury for myself in order to buy something for my students or classroom. Building my adult life is hard when almost my entire month’s income barely covers the bills. I am unable to save for my wedding or the family we hope to have some day.”

Young educators talk about this dilemma a lot and sometimes try to justify the struggle by acknowledging that teaching isn’t so much a career choice, but a calling. “You have to be called to teach,” Alexandria said, “otherwise it may be discouraging and overwhelming and those emotions could spill over to students.”

But sometimes that justification is hard. “My fiancé’s weekly check is significantly more than my biweekly check and his tools and resources are provided,” said Chelsey.

“Plus,” she added, “he works an eight-hour day with no additional workload at home or on the weekends. This is part of the conversation when educators choose to leave the profession — that other professions have better working conditions that come with better pay. I would have to choose between being a teacher or being homeless if I didn’t have my fiancé’s extra support.”

What this report finds: The teacher pay penalty is bigger than ever. In 2015, public school teachers’ weekly wages were…www.epi.org

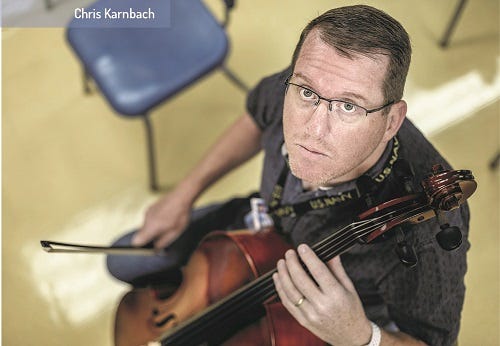

For veteran St. Mary’s County music teachers Anne-Marie and Chris Karnbach, continuing in the profession is a conscious choice — acknowledging the calling and accepting the rewards, even as other opportunities beckon.

Both are orchestra directors who love sharing the thrill of mastery and performance. “I love making music and I love passing that love on to my students,” said middle school teacher Chris.

“It’s been almost 19 years and I still get giddy when class starts,” Anne-Marie, a high school teacher, said. “I love seeing that enthusiasm in their eyes when they discover they can do something, or something they have been working on sounds great.”

Chris has a second job in the Navy as a senior chief petty officer and that helps with expenses for their family of four. “I went to college with a former band teacher here in the county. She gave up teaching and works now for BAE Systems, the aerospace company. She knows what I do in the Navy and offers me a job all the time. I wasn’t home from Iraq for more than three months before I was offered three jobs.

“To be honest, I stuck with what I love doing,” Chris said.

Teachers have been fighting for higher wages in states like West Virginia and Oklahoma. But cash-strapped states don’t…time.com

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, he’s among the nearly 18% of US teachers working a second gig (the study didn’t include coaching or other extra-curricular activities as part-time jobs). That figure, says the news website Vox, is the most in 10 years and even more than during the Great Recession. Compare that to the national average of full-time workers with second jobs, and you’ll find that teachers are five times more likely to work a second job.

“I’ve been asked more than once: why are you still teaching?” Chris said.

Maryland has the highest median household income in the nation (and with it a larger tax base) — but it does the worst job in the Mid-Atlantic at making teaching competitive with other jobs in the state’s economy. Maryland teachers make 84 cents on the dollar — a teacher pay penalty of 16 cents for every dollar earned.

Chris thinks one reason for the disparity in pay with other equally credentialed professions is that education shows no immediate payback. “Our impact is usually shown further down the line. People don’t understand that what you do to teachers today will affect students tomorrow. Cutting funding won’t change this year’s graduation rates or test scores, but it will sure show up down the line.”

For educators to gain more respect, there needs to be a systemic change in philosophy towards school. This can happen by building and nurturing stronger relationships with the communities and stakeholders,” said elementary educator Colleen McCray. “Research has proven that when there is a strong educational system in place, the entire community benefits.”

OKLAHOMA CITY — The anxiety and seething anger that followed the disappearance of middle-income jobs in factory towns…www.nytimes.com

Building community is important to Colleen and her husband Keith McCray, both Washington County elementary teachers. Keith, a former police officer, wanted a safer job after they had their first child and when Colleen pointed out that teaching was a great way to continue to contribute, he took the bait.

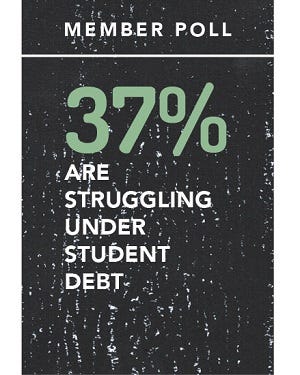

They both have two master’s degrees, and, said Colleen, “Right now, the return on investment is terrible. We’re required to continue our education and only reimbursed for part of it. The increase in salary is negligible when compared to the increase in debt.”

But, she said, “We wouldn’t change any of it. Our students have better teachers because of our hard work and learning. But teachers are simply not paid enough for the work that goes into the job. Not just for the post-graduate work that we’re required to do, but for the time we put in. The planning, the prep, the extra courses — we’re never done.”

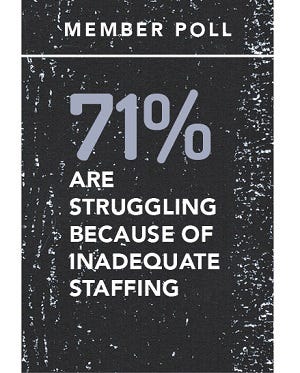

The $2.9 billion annual underfunding of Maryland schools takes its toll in every building and community and perhaps nowhere is it more deeply felt than in the staffing crisis. MSEA’s survey found that 71% of educators believed their school had inadequate staffing.

“Expectations are consistent despite the enrollment and needs of a school. The current funding formula doesn’t adequately allow for the special circumstances within each individual school,” says middle school teacher Chris Stefanizzi–Greenwood, Frederick County. “When cuts are made to reduce ‘non-essential’ personnel, no one seems to recognize that there is no ‘non-essential’ staff in a school with extreme challenges.”

ESP jobs have declined while district leader and supervisor jobs have grown at 10 times the rate of teacher positions.mseanewsfeed.com

Her colleague Crystal Dorsey agrees. “It is not unusual to have 10+ students in a room who are in need of some type of learning accommodation. More staff and support would allow for a larger base of differentiation within the classroom and ultimately help all students.”

We have a perfect storm of increased enrollment, workload increases, changing demographics, and school needs without the human resources to meet them,” adds Chris.