How Can We Be So Wrong About Professional Development?

8 ways workshops fail and how Japan gets it right

By now, it’s pretty clear to everyone involved: good professional development is something every educator wants and needs, but few experience PD that is rich, deep, and meaningful.

In a 2013 report called “Teaching the Teacher: Effective Professional Development in an Era of High Stakes Accountability,” the Center for Public Education (CTE) called the mainstay one-stop workshop model “abysmal.”

Stanford University’s Linda Darling-Hammond and the School Redesign Network (SRN) said in 2009’s “Professional Learning in the Learning Profession” that an event that “involved a limited amount of professional development (ranging from 5 to 14 hours) showed no statistically significant effect on learning.”

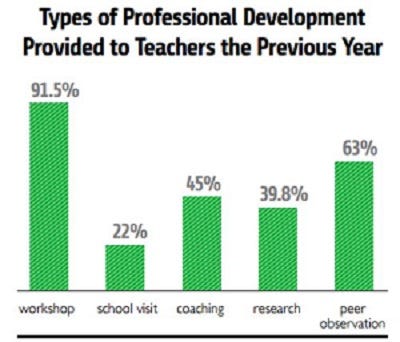

Despite those findings, and the accompanying research that defines what good professional development looks like, the one-stop workshop remains the most common. And as you’ll see below, two of the most effective PD activities — research and coaching — lag way behind.

Want good PD? Look for these 8 characteristics

Let’s take a look at the characteristics that both the Center for Public Education and the School Redesign Network have established as the standards for good PD. Then we’ll look at a successful model long used by Japan’s educators that fulfills each of them.

- The duration of professional development must be significant and ongoing to allow time for teachers to learn a new strategy and grapple with implementation.

Some studies have concluded that teachers may need as many as 50 hours of instruction, practice, and coaching before a new teaching strategy is mastered and implemented in class. — The Center for Public Education

2. There must be support for a teacher during the implementation stage that addresses the specific challenges of changing classroom practice.

3. Teachers’ initial exposure to a concept should not be passive, but rather should engage teachers through varied approaches so they can participate actively in making sense of a new practice.

4. Modeling has been found to be highly effective in helping teachers understand a new practice.

On average, it takes 20 separate instances of practice for a teacher to master a new skill, and this number may increase if a skill is exceptionally complex. — The Center for Public Education

5. The content presented to teachers shouldn’t be generic, but instead specific to the discipline (for middle school and high school teachers) or grade-level (for elementary school teachers).

6. Professional development should focus on student learning and address the teaching of specific curriculum content.

7. Professional development should align with school improvement priorities and goals.

8. Professional development should build strong working relationships among teachers.

Deep, meaningful PD — Japan’s lesson study model

It’s not drive-by and it’s definitely not sit-and-get PD — Japan’s lesson study model is embedded, long-term, collegial, specific, and student focused. This one model meets every one of the eight standards listed above.

Read this story on Japan’s lesson study and learn how and why it’s the opposite of the one-day workshops you’ve attended.

Here’s a simple 5-step example of how one might work:

1. Four to six teachers gather to solve a teaching problem that is common to them all.

2. They dig into the latest education research to discover why the problem exists and study why existing methods aren’t working.

3. One teacher delivers the research lesson as the other group members observe all aspects of the lesson, take notes, and perhaps video or audio tape.

4. During the lesson, the other group members gather and observe evidence. They don’t focus on the teacher’s performance, instead, they look to the students to determine what’s working and what isn’t.

5. Follow-up can take weeks or months as group members meet after the lesson to dig deep and refine it, and even study the revised version to further improve it.

Sue Wilder, a national education consultant at the Developmental Studies Center introduced lesson study this way to a group of American teachers: “We are going to work on a lesson and it’s going to be the best lesson we can prepare based on what we know right now and we’re going to try it out.

“Then we’re going spend the time really collecting data on the students and then we’re going to come back and analyze that data and see what in the lesson worked and what in the lesson might we do differently in order to get the desired outcome.” Watch Wilder go through the lesson study process with a group of American teachers in the video.

“Using lesson study to plan lessons is a really powerful way to bring teachers together to plan lessons that they really can’t do on their own,” explains Peter Brunn, director of professional development for the Center for the Collaborative Classroom. “Lesson study allows the teacher to sit with colleagues to reflect on one specific lesson in time and use that as an opportunity to grow their thinking about teaching and learning.”

Have you participated in professional development as deep and thoughtful as lesson study? Tell us in the comments below.