Gen-Nexters in the Classroom

Supported. Respected. Staying.

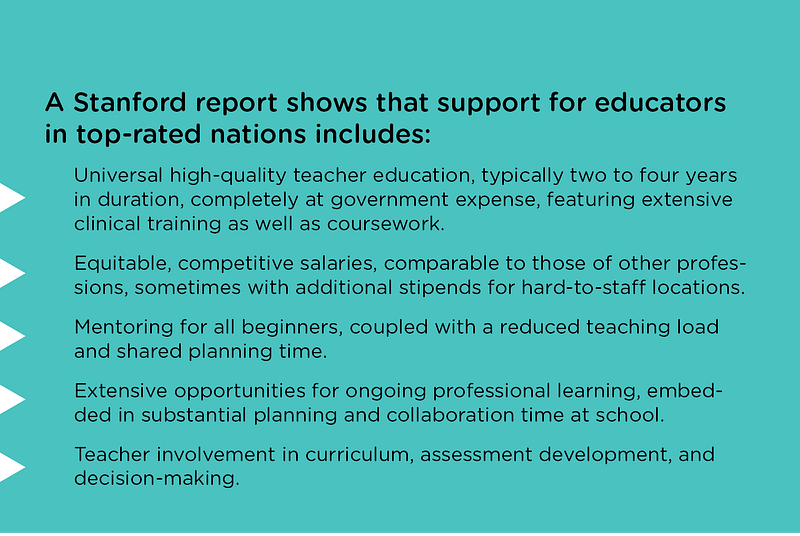

In Finland, a primary teacher must study at a university for five or six years in a program that includes not only pedagogy, but units on neuroscience, curriculum theories, and research methods. They must then take a clinical practical training at the university’s teacher training school.

In Singapore, every new teacher is assigned a master teacher mentor for several years. Master teachers are found in every school in Singapore, coaching and developing the skills of new and veteran teachers. Teachers there have 20 hours each week to devote to working with colleagues and visiting one another’s classrooms for observation and inspiration.

In South Korea, teachers who have completed three years in the classroom can enroll in a five-week, 180-hour government-approved professional development program and receive an advanced certificate. The certificate brings a salary in- crease and eligibility for promotion.

The biggest ever global school rankings have been published, with Asian countries in the top five places and African…www.bbc.com

Singapore, Sweden, and the Netherlands require at least 100 hours of professional development per year, in addition to hours of collegial planning and inquiry.

These are just some of the standards for teacher support in the highest achieving countries, according to a report by Linda Darling-Hammond and the Stanford Center for Opportunity in Education. What do they have in common? A national commitment to high-quality public education. Respect for the complex craft of teaching. A willingness to provide the resources and supports that good teachers need to succeed.

Great. Big. Differences.

Look at the difference between those countries and the U.S. in professional development alone — the Learning Institute reported in 2010 “that professional development activities of under 14 hours appear to have no effect on teachers’ effectiveness. Meanwhile, well-designed content-specific learning opportunities averaging about 50 hours over a 6 to 12 month period of time were associated with gains of up to 21 percentile points on the achievement tests. Fewer than 20 percent of U.S. teachers receive this kind of professional development.”

The question, “Why don’t we train teachers the same way we train doctors?” isn’t a rare one. Just in recent years, we…mseanewsfeed.com

In countries like Finland, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Norway the teaching profession is respected and the standards for preparation are high — and they rarely experience the kind of teacher shortages that have left much of the U.S. with overcrowded classrooms and overtaxed professionals.

As every educator knows, here in the U.S., the teaching profession is less lauded and less supported on almost every level. Funding crises are the norm in nearly every state. Educators across the board are asked to do more with less. And for young and early career educators the first months and years are mostly a shock as they try to parse expectations versus reality.

Supporting? Sort of. Sometimes.

MSDE acknowledges that 47% of educators who completed nearly two years of teaching leave the field before their third year. Why? Pay, workload, expectation versus reality, lack of respect, lack of autonomy, and lack of supporting mentor and induction programs that are meaningful and deep. Some new teachers, like Jasmine Stewart, a chemistry teacher in Prince George’s County, receive encouragement and support from colleagues, and administration — including, for Stewart, a New Teachers Academy in her school.

But, she said, it is the Towson University master of arts in teaching program and a year-long clinical internship that she values the most. “My last year in the field truly prepared me. I was paired with two great mentors who sort of threw me directly into their classrooms. Those experiences helped me to have a successful first year.”

Stewart discovered her experience was not the norm. She, her Prince George’s County colleague Kyle De Jan, Robin Beers (Anne Arundel County), and Henoch Hailu (Montgomery County) were Educators in Residence at MSEA’s headquarters in Annapolis this summer. All early-career educators, they studied the status of new teach- er induction programs in Maryland, the results of the 2015 TELL Survey, MSDE documents, surveyed hundreds of Maryland educators on their mentoring and induction experience, and interviewed early career educators in nearly every county. What they found is a telling portrait of where the rubber meets the road for Maryland’s support of new teachers.

Prep, Pay, Support, Respect, Status, and Working Conditionsmseanewsfeed.com

Regulations? What regulations?

COMAR — the Code of Maryland Regulations — mandates that Maryland school systems have programs in place to increase the retention rate of teachers. It also requires that local school systems provide an orientation program before the school year begins for all new teachers, ongoing support from a mentor, regularly scheduled opportunities to observe or co-teach with skilled teachers, ongoing professional devel- opment, and ongoing formative review including observations and lesson plan feedback. COMAR also recommends a reduction in workload for every new teacher and guidelines for mentor selection. Was that your experience?

These promising mandates may be in code, but in reality, there is little accountability for districts and so implementation has faltered in many places and left new educators to struggle.

“The quality and characteristics of new educator support programs vary widely in our state due to vague COMAR recommendations,” said Educator in Residence Robin Beers. “This means that new teachers are not necessarily getting the support they need to make it through their first few years on the job. Effective mentoring can make or break a new teacher and is critical to teacher retention.”

Just look at the results of the 2015 TELL Survey, which over 30,000 Mary- land educators responded to: more than 25% of new educators were not provided a formal mentor nor professional development specifically target- ed to new educators; more than 85% received no reduction in workload; more than half were not given release time to observe veteran colleagues; and more than 30% did not have opportunities to access a professional learning community to collaborate with colleagues.

What can help?

There are fixes. Recommendations from the New Teacher Center (NTC) on effective teacher induction policies are specific — they are multi-year; set stringent policies for the mentor pro- gram; offer differentiated professional development based on need; and define what is considered successful completion of an induction program. NTC’s recommendations — and the examples of high-achieving countries — set a roadmap for ways to move forward in Maryland.

“Teachers in their first through fifth year are the largest group of teachers in Maryland. If we’re getting off to a rough start, without the supports other countries have proven to be successful — many of which our own regulations recommend — of course some of us will look elsewhere,” said Henoch Hailu, an MSEA Educator in Residence.

“The work of our Educators in Residence points to the gap between where we are and where we need to be,” said MSEA President Betty Weller. “We have work to do at the state level to improve the guidance and guardrails the state provides to ensure that mentoring and induction programs are high quality.

And we have work to do locally to get more contract language that gives new educators the time, support, and re- sources they need to be successful and become confident veteran educators.”

The analysis of the Educators in Residence found some clear areas of concern: only six school systems met the COMAR-recommended ratio of one mentor for every 15 educators; a distinct lack of mandatory professional development for administrators on how to best support early career educators; and inconsistencies between counties in terms of induction program components and mentor selection and training, to name a few. Some of these challenges may be able to be addressed locally; for others, state legislative action may be a more effective route.

MSEA at work

As MSEA investigates the potential for state legislative action during the upcoming General Assembly session, local association bargaining teams can begin work right now to encourage their districts to adhere to the COMAR-recommended reduction in workload for first-year educators.

This can include relieving first-year educators from serving on committees; recommending that these educators are excused from non-instructional duties when possible; encouraging departmentalization at the elementary level, which positively impacts individual teacher content planning; recommending that first-year educators not proctor standardized tests that are not for their own students or grade level; and advocating for substitute funds to provide first-year educators with additional individual or collaborative planning with their mentor or team.

“Teachers in their first through fifth year are the largest group of teachers in Maryland. If we’re getting off to a rough start, without the supports other countries have proven to be successful — many of which our own regulations recommend — of course some of us will look elsewhere,” said Henoch Hailu, an Educator in Residence. “But most of us are in it because we believe in public education and the potential of our students. All of us in the field should work for more support for ourselves and our colleagues just beginning their practice.

“We know what we need. Now we have to fight for it.”