Dual Pandemics: COVID and Closure, Race and Equity

The heart of MSEA is our members—education professionals who join together locally and statewide across a large number of job descriptions for the purpose of protecting and improving public education for students, families, and our communities. MSEA members are the strongest employee union in the state—we pivot from our positions as dedicated frontline educators to informed frontline activists with a text, phone call, or email call to action. Our work passing the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future and halting Gov. Hogan’s recent education cuts are only the most recent proofs of our organizing and mobilizing power.

A nd now, as we face what Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture and now secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, calls the dual pandemics of coronavirus and systemic and structural racism, educators across the country are standing up for the health, safety, and emotional well-being of their students and communities. This intersection, Bunch says, “is like no other in American history.”

To meet this intersection, we are all watching and waiting for more universal signs of recovery from the coronavirus, practicing the social distancing and good hygiene we know to be vital, and challenging ourselves with the new demands of virtual learning. But we are also witnessing broader awareness of systemic racial injustice and its heartbreaking consequences.

There is always room to grow, learn, and discover—to find in ourselves the humility, openness, and heart to be and do better.

Finally, the nation is catching up with what many have long known—you can’t say “all men are created equal” and underserve and underfund education. It’s true, MSEA has a long tradition of rallying for and helping to pass equitable funding and strong supports for students and educators through statewide funding like the Blueprint, opposing dangerous standardized tests that for so many years left strong students behind because of the white-centered contexts, and strongly advocating for cultural competence, restorative practices, fair discipline policies, reducing suspensions, and equitable opportunities for all students.

But there is always room to grow, learn, and discover—to find in ourselves the humility, openness, and heart to be and do better. President Cheryl Bost wants to maximize the union’s impact on these issues through a new member-led, statewide Council on Safe, Healthy, and Supportive Teaching and Learning Environments.

“We’ve already seen how the coronavirus has challenged education norms at the same time that our country’s racial crisis has deeply challenged how we perceive and act upon our role in the injustices Black and Brown students and families suffer,” says Bost. “Because of this intersection, our experience and professional training places us at the frontlines, again, to lead the way.”

The new council will be led by MSEA members and study five education-centered areas: mental and behavioral health and trauma-informed best practices; teacher preparation and educator continuing education; school, student, and educator safety; restorative approaches and best practices; and implicit bias and culturally responsive pedagogy, practice, and instructional content. Its charge will be to affirm and recommend initiatives MSEA can advance through legislative, policy, and regulatory avenues, collective bargaining language, and member programing and advocacy aimed at creating and sustaining safe, healthy, and supportive learning environments for our students and working conditions for MSEA members.

“As we take this deeper look at these issues of racial and social justice and the role of educators and public education in them,” Bost says, “I hope all members will join me in examining our own biases and how we can all strive to become the informed, supportive, anti-racist educators all of our students deserve.

“I know many of us are already working hard on these issues. Learn more about our position on school reopening and read member voices on the dual pandemic below. Let’s move forward together.”

“A perfect solution does not exist. A safe one does.”

On July 14, MSEA, the Baltimore Teachers Union, and the Maryland PTA issued a joint call for the fall semester of the upcoming school year to be virtual. Together they sent a letter, which you can read at this link, to Gov. Hogan and State School Supt. Salmon, asking them to protect the health and safety of Maryland students, educators, and families.

MSEA President Bost, BTU President Diamonté Brown, and Maryland PTA Vice President for Advocacy Tonya Sweat held a joint virtual press conference on July 14, to publicly announce the position.

Be an Anti-Racist

As a graduate and young early career educator in Charles County, I have a dual perspective of the effects of race in the classroom.

C. Paul Barnhart Elementary School, Charles County

As a student, I felt as though racism wasn’t discussed and addressed in school. Black history lessons were simplified, beginning with tory slavery and ending with emancipation. That’s all. Textbooks rarely had pictures of students who looked like me or scenarios that I made connections with. The staff was made up of primarily white females and lacked diversity. I was left in the dark of the richness of my history because I was left out of curriculum. I struggled with making connections between my culture and my education. I was delighted when I saw staff who looked like me and/or who wanted to create a deeper relationship with me.

As an educator, I took those same experiences and challenged myself to create a culturally responsive classroom and build relationships with my students. I sought to learn about my Black history so that I was able to share it with others. Children and adults are aware of the changes in society—we’re experiencing both a pandemic and a racial crisis. I felt it important to check in with my students and team members to see how they were doing mentally because I was experiencing such feelings of pain and sadness as I watched history continue to repeat itself. I can only imagine how others were feeling. I asked myself: what I can do to support my students and staff at this time? How can we stand up for justice in education?

Kayla Moore, another early career educator and MSEA member, and I share like-minded ideals on anti-racist education and creating a classroom environment where all children are seen room and heard. As educators, we are tasked with helping educate and guide our students through academic and social development, but now, with a heightened consciousness and interest in racism, injustice, and bias within the education system, we are taking a proactive approach toward anti-racist education. ward

What does it mean to be an anti-racist educator? To be an anti-racist educator means you are taking action to dismantle racism in schools, classrooms, and communities. An anti-racist educator participates in ongoing training and planning to ensure they are creating a culturally responsive environment for staff and students along with confronting racism at the core. An anti-racist educator takes initiative in seeking to fight injustice.

We, as anti-racist educators, must educate ourselves about the historical events that have created structural and institutional racism, redlining, oppression, microaggressions, the denial of equity in education, issues that have led us to where we are now. We must better unled understand these injustices.

As Kayla and I took action on the frontlines protesting for the Black Lives Matter movement, we realized it was important to us to create a safe space where educators could discuss what being an anti-racist educator really means, learn more about Black history, and take steps to creating truly culturally responsive classrooms for every student. By educating ourselves, we will have a better understanding of our role as anti-racist educators and be better advocates for our students and ourselves.

MSEA developed the “How to Be an Anti-Racist Educator” webinar series, which was delivered in part by MSEA members. Part 1 included small breakout sessions where educators explored the levels of racism. I facilitated one of the breakout sessions along with three other members. The breakout sessions provided opportunities for educators to discuss concepts learned during the session by having courageous conversations about race. Part 2 will be held on August 26., and Part 3 will be held on October 28. The webinar series is one of the many opportunities educators can take to educate themselves, students, and others about what being an anti-racist means and how we can all become one.

Assume Nothing

With so many conversations about the reopening of schools over Zoom and Google Meet, I often wonder if there are equally as many conversations happening about the needs of students that do not involve masks or hand sanitizer—the social and emotional needs that will inevitably present themselves when we return to instruction no matter what form it takes. How ready are educators to acknowledge and address these needs of our students? Who is having the discussions about the mental health support our students will need when they walk back through the real or virtual school doors?

When schools closed and teachers and students quickly moved to crisis virtual learning, there were several immediate implications of this sudden way of life, among them the loss of human connection that everyone needs to thrive mentally and emotionally and the loss of a safe and supportive space for students for whom schools were their only safe haven. During school closure and this summer, many experienced neglect, hunger, and abuse on top of the added stressors of virtual learning and the fear of a parent or family member getting sick.

No matter how and when we are together again, schools and school districts must have a plan in place that will allow our students to unpack the traumas they experienced during this unprecedented time. We must acknowledge that when students return to school, they may be in a totally different mental and emotional space than when they left in March.

Not only have all students been dealing with the uncertainty of school and the coronavirus during quarantine, Black students are experiencing the added trauma of racial tension heightened over the horrific death of George Floyd and police brutality, and the news that illness and death from the coronavirus among Black people was disproportionately higher than among white people.

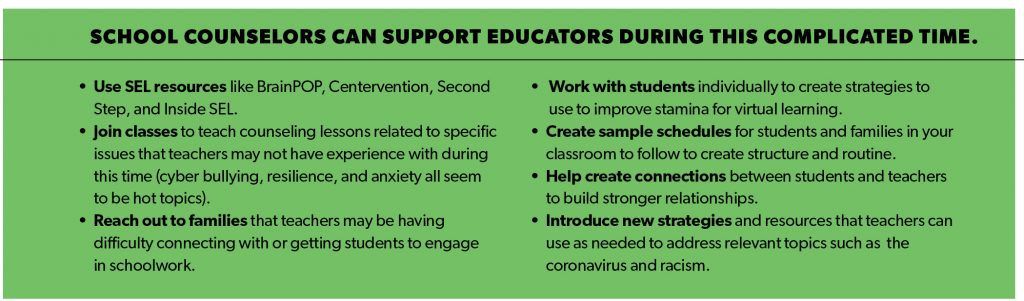

When we are with our students again, we must be prepared with social and emotional learning tools (SEL) and restorative practices (RP), as well as mental health options for both children and educators. Using these tools can help us all process our complicated feelings about the closing of schools, the pandemic, race, and how we are experiencing the Black Lives Matter movement and the marches, rallies, and protests supporting it.

No matter how and when we are together again, schools and school districts must have a plan in place that will allow our students to unpack the traumas they experienced during this unprecedented time.

Both SEL and RP, when used in the learning environment, can prepare students for academic success after a hiatus from school. Talking circles and listening circles provide students with a space to be included and heard. The alignment of SEL and RP teaches skills such as identifying emotions, taking in others’ perspectives, developing empathy, and self-reflection while participating in the circle process. Every student gets the opportunity to tell their story and actively listen to the stories of others.

Every educator must be prepared to check any bias they may have about what they think Black children are dealing with and experiencing. We cannot assume that every Black child is dealing with the same trauma or loss, or is experiencing the same trauma in the same way. We know that many of these students may also be experiencing their caregivers’ stress over losing their jobs, facing the terrible trauma of eviction from their homes, and/or the loss of a family member or friend from the coronavirus. We must take the time to see each Black child as the individual they are and make every effort to understand the issues they are bringing back to school when they return.

These crises will forever define our students’ lives. We must honor their experience and take this opportunity to create stronger and more intentional school communities of care, connectivity and healing for them.

Adapt, Grow, Connect

As a new elementary school counselor, school closure and virtual learning have presented me with unique and unexpected challenges. It forced me to quickly adapt and grow as a professional. I found myself connecting with students in brand new ways—counseling sessions on Zoom through mom’s cell phone, virtual mini-sessions with families, participating in home scavenger hunts, feelings check-ins through emojis, and several hours of phone calls. I never thought I would hear the statement “I want to go back to school!” from so many eager young learners longing to be back with their friends.

Pangborn Elementary School, Washington County

This aspect of social isolation is perhaps the most concerning impact of the coronavirus on students. Many students aren’t able to play or socialize with peers in any capacity and that’s a critical aspect of cognitive development for young students. Many of our students will likely take steps back in their ability to form friendships and regulate emotions. We can also expect their behaviors to worsen due to lack of structured play and routine. The role of school counselors will be more important than ever as we address these gaps in the upcoming year whether virtually or in person.

This isolation makes it vitally important that educators form the critical, meaningful educator–student relationships we know are essential to students’ mental health, well-being, and learning. We’ve done it in person … and doing it virtually is possible. Here are some helpful tips to make that connection:

• Be very intentional about incorporating ways that students can interact with you and other students throughout the day. This could be games, reading aloud, virtual circle time, sharing work, etc.

• Don’t forget about brain breaks! Although we may not be in the classroom, our students still need breaks to move, rest, or laugh. GoNoodle is my go-to for movement breaks. You could also try deep breathing or mindfulness videos if you feel the class could use a mental break.

• Create themed days that will be engaging and exciting for students. Hat Day, Neon Day, Crazy Hair Day, or Career Day are just a few ideas!

• Lunch bunches are a great way for students to be able to connect with their peers. Give the class free, unstructured time to interact with one another. I’m sure you’ll get some laughs just listening in.

Not only are our students living through a global pandemic, many have also been exposed to recent events related to racial injustice and inequality. Students of all ages and backgrounds will likely return to us with new trauma, anxiety, feelings of isolation, and will have lots and lots of questions. As educators, we must be prepared to step up to the plate and find ways to support and uplift all of our students in an equitable manner.

I am committed to promoting the virtues of unity, respect, and kindness, and making school—wherever it takes place—feel like a safe place for everyone. The upcoming school year will be full of new challenges, but I am embracing the opportunity to support and empower all students, every day.

Finding Safe Places

As a school psychologist, my very first thought after the death of George Floyd was “I need to talk to my students about these events as soon as possible.” But I couldn’t. This inability to interact with them about the events of these past several months hurts deeply because I know they have strong feelings and lots of questions—many of them have experienced racial and historical traumas. Let’s put this into context: our students were trying to cope with the threat of coronavirus and the deaths of family, friends, and community members in addition to traumas they were already trying to heal from, including isolation from their peers. They watched the very minute George Floyd’s life left his body. And they watched dismissive pundits and political debate over a phrase as affirming and fundamental as “Black Lives Matter.

What can we do as educators to help our students? For starters, let’s acknowledge that there is racial inequity and disproportionality in education and that there are systems in place that continue to perpetuate inequality and the lack of access to opportunities. Let’s be honest while educating our students about the history of this country and its legacy of racism, police brutality, and racial profiling. Let’s identify these experiences for what they are—traumatic. Then, let’s create the safe space we all need to facilitate competent education and discussion about racism.

Our students experience more than they express and more than adults realize. Many of our students come from communities where they experience racism and police brutality on a daily basis. We must acknowledge feelings of anger, anxiety, fear, sadness, frustration, and confusion. Let’s give our students multiple structured ways to express themselves amongst their peers or in a smaller setting with a trusted professional. This requires mental health professionals, parents, and the community.

My own education on racism, profiling, and police brutality took place in those spaces. My parents taught me that being Black in America meant having to work harder to reach and sustain the same level of success as my white counterparts. They taught me about self-advocacy and speaking up for others who can’t defend or speak up for themselves.

This education helped prepare me for the world we live in. My teammates and I were called racial slurs by opposing players and their fans. I was illegally detained by campus police in college. I was stopped and frisked by the NYPD many times for “looking suspicious.” I confronted former administrators in Ohio who said they didn’t trust a young Black school psychologist. I confronted a teacher who referred to me as “boy.” I had conversations with colleagues who didn’t understand why telling me, “you’re so articulate” was a microaggression.

Too many of our students are not given the same education or opportunities I was to respond safely to those affronts or learn about, process, and stand up to racism. But that doesn’t mean we can’t come together now to teach young people about the history and current realities of systemic and overt racism and give them hope that they, too, can learn, thrive, and be successful in school and beyond.

Never underestimate the power of an educator

Mrs. Roseberry, my 7th grade English teacher, became a teacher-mom to me and countless other students because she occasionally took breaks from the lesson plan to speak to the class about racism, prejudice, and Black history. Sometimes she tied it into the curriculum. And while she was an amazing and nurturing teacher, she was also very firm and pushed us to do our best because she knew what we would encounter in the real world.

A Brief Anti-Racism Glossary

ANTI-RACISM The work of actively opposing racism by advocating for changes in political, economic, and social life. Anti-racism tends to be an individualized approach and set up in opposition to individual racist behaviors and impacts.

ASSIMILATIONIST One who expresses the racist idea that a racial group is culturally or behaviorally inferior and is supporting cultural or behavioral enrichment programs to develop that racial group.

BLACK LIVES MATTER (BLM) is a decentralized movement in the United States that advocates for non-violent civil disobedience in protest against incidents of police brutality and all racially motivated violence against Black people. BLM was formed by three Black women—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who killed Trayvon Martin.

CULTURAL APPROPRIATION Theft of cultural elements for one’s own use, commodification, or profit, including symbols, art, language, customs, etc. often without understanding, acknowledgement, or respect for its value in the original culture.

DEFUNDING THE POLICE The policy of reallocating a portion of funding and resources from law enforcement to community-based programs that provide social workers, mental health professionals, and health care services.

INTERSECTIONALITY How race and gender and other social and political identities can produce different sets of privileges and disadvantages.

MICROAGGRESSION Subtle or indirect instances of racism. For example, colorblindness is a form of microaggression because it ignores a person’s ethnic identity.

NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE A slogan used to emphasize that peace cannot be achieved as long as racial injustice exists.

PERFORMATIVE ACTIVISM Ingenuine activism to gain political clout.

PRIVILEGE Unearned social power accorded by the formal and informal institutions of society to ALL members of a dominant group. Privilege is usually invisible to those who have it because we’re taught not to see it, but nevertheless it puts them at an advantage over those who do not have it.

SOLIDARITY The support for people with whom you have a common goal. The person showing their solidarity through action is an ally. Accomplices elevate the ally role by dismantling the systems of oppression.

Sourcess: racialequitytools.org; dailybruin.com

Member-Recommended Anti-Racist Resources

Find these accessible online resources recommended by members at MSEA’s webinar How to Be an Anti-Racist Educator, Part 1. Look for Part 2 on August 26!

Websites and Documents

Anti-Ableism and Disability Education Drive

Culture Queen, Facebook Culturally relevant book and song lists for kids.

Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity

Public Systemic Racism Library

White Privilege Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

Video

How Microaggressions Are Like Mosquito Bites

Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man Emmanuel Acho

Visit our Facebook page to find MSEA’s Learn More at 4 recorded live with special guests:

Books

Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt

Culturally Relevant Teaching and Learning Dr. Geneva Gay, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings

The Guide for White Women Who Teach Black Boys Eddie Moore, Ali Michael, and Marguerite Penick-Parks

How to Be an Anti-Racist Ibram X. Kendi

Piecing Me Together Renée Watson

Race Matters Dr. Cornel West

Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism, and You Ibram X. Kendi

What If I Say the Wrong Thing? 25 Habits for Culturally

Effective People Verna Myers

White Fragility Robin DiAngelo

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum

Podcasts

Intersectionality Matters!

Leading Equity Podcast

NPR 1A

Whistleblower Rules

Don’t be afraid to speak up.

If your workplace is not following coronavirus mitigation protocols to protect your health and safety, there are specific whistleblower protections that prohibit employers from retaliating against educators for reporting conditions that are a substantial danger to public health or safety or that provide information to a state agency such as the Maryland Occupational Safety and Health Division (MOSH).

Your first stop in reporting is the school system. If you don’t get results, go straight to your union.

The union can help in reporting and organizing a communication and information campaign to be sure the school system is aware of unsafe or unhealthy conditions. Your union can file a grievance under the collective bargaining agreement, or even file a complaint with the Commissioner of Labor and Industry that is responsible for promoting and enforcing safe and healthy work environments. There may also be some circumstances where an employee may refuse to report to a work area if there is no reasonable alternative in order to avoid a situation that may result in serious injury or death.

Before you or a colleague takes such action, we strongly recommend contacting your local UniServ director and at the same time file a complaint with MOSH, which can seek an injunction against the employer or a grievance.