Creating Community with Peace Circles

Ninth grade U.S. history teacher Robin McNair is a believer in restorative practices. “Just one suspension doubles a child’s chance ofu2026

Ninth grade U.S. history teacher Robin McNair is a believer in restorative practices. “Just one suspension doubles a child’s chance of entering the school to prison pipeline. The use of these practices have decreased suspensions and expulsions, reduced the number of referrals, and improved graduation rates. They are game changers.” McNair, a member of the Prince George’s County Educators’ Association (PGCEA), has studied and trained colleagues on restorative practices and has seen her own students transformed by using them in her classroom.

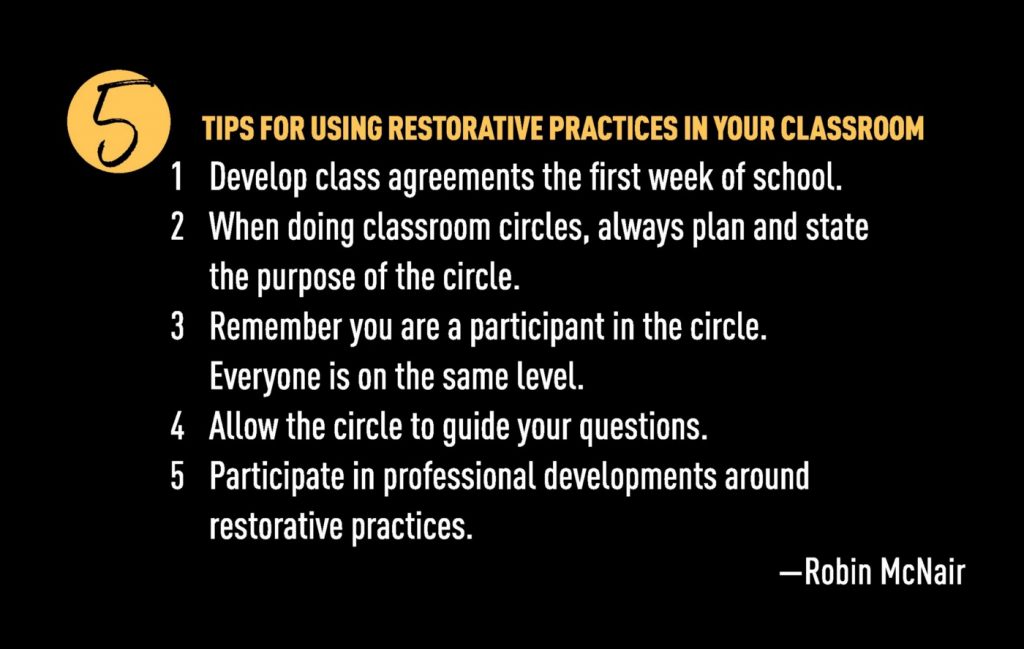

PGCEA members like McNair are driving the restorative practices movement in the county. When the local’s Discipline Review Committee recognized restorative practices as teacher-level intervention in 2013, McNair, the chair of the committee, set out to learn everything she could about the movement and in doing so, became a powerful advocate.

“Restorative practices aren’t only for use after a conflict or incident. These practices allow us to proactively build community within a classroom and within a school by nurturing relationships between teachers and students,” McNair said. “When students know that you care about them they are more likely to follow the rules and more likely to stay in the classroom and do the work.”

“When you build that community and create an environment of safety, students open up and you learn about what makes a child tick, what makes a child happy, and what makes a child sad. In a community, you can focus on the social and emotional development of the student and their needs, and ultimately help them academically.”

The work McNair and PGCEA spearheaded has become the foundation for the county’s educator training on restorative practices, thanks to the buy-in from county schools CEO Kevin Maxwell and union–management collaboration. With support from NEA from the start, PGCEA has completed three four-day trainings resulting in over 40 formally trained educators from 21 schools (including the director of student services and PBIS coordinator) now putting restorative practices to work in their classrooms and schools. But like most counties in the state, there is no formal restorative practice framework in Prince George’s County yet. The goal is to have 7–10 schools pilot restorative practices next year with hopes for funding for the formal educator training critical for the practices to be put in place successfully.

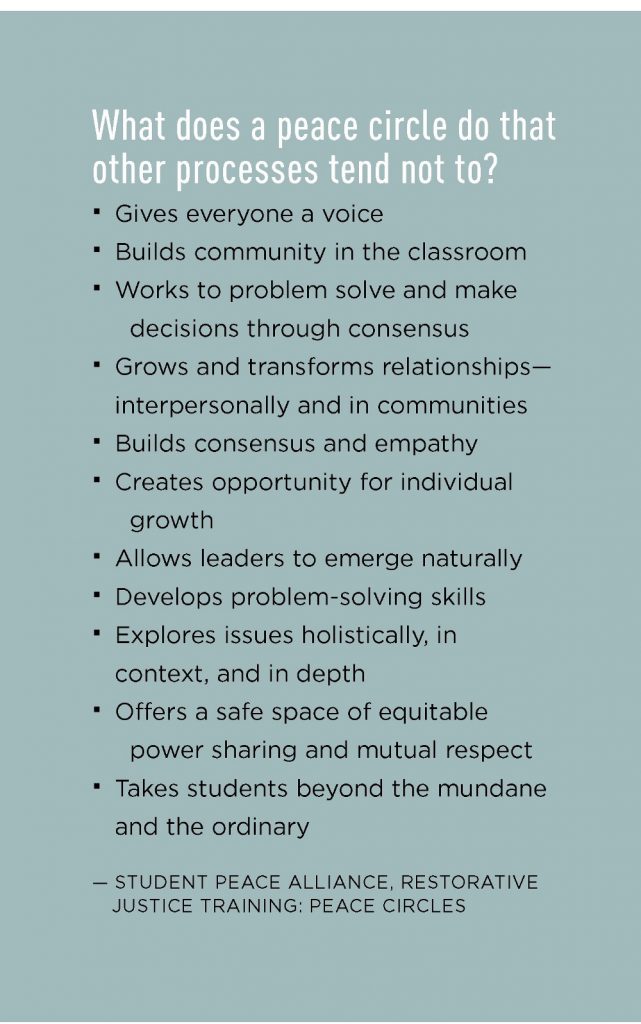

McNair believes that community building starts in the classroom, and for her adolescent students the peace circle has become a safe haven. There are many kinds of circles within the restorative practice model — some are called proactive circles, others are called community building, celebration, and repairing circles. They are all versions of the peace circle — the circle process of the North American indigenous cultures that is rooted in community sharing, ritual, openness, acceptance, respect, and resolution.

Through circles, McNair has created the clear agreements and authentic communication that is the foundation of every restorative practice and high–functioning community no matter how large or small.

For McNair, the first step toward creating each class community is writing with her students the “respect agreements” that make up the honor code for each of her classes. They are posted and referred to as necessary to help keep students focused on instruction. When someone violates the code, she refers to the broken rule by number and doesn’t call out the student by name. Because writing the code was a collaborative effort, everyone in the room takes ownership and is accountable.

“Students want to be heard and this gives them a voice — immediately. When I refer to our agreement, I don’t have to shame anyone. Instead of losing instructional time, I simply refer to the code and in 10 seconds I’m right back to teaching.”

With the code in place, McNair and her students embark on their journey of authentic communication — the peace circles she holds every Friday. Students are stunned at the idea of a safe place where sharing and understanding are the currency. This year, bewildered ninth graders stepped cautiously into her classroom now arranged in a wide circle. Using words like respect, honor, solidarity, community, universality, giving and receiving, power, and perfect democracy, she quietly introduced the circle concept, the several talking pieces in the center of the circle, and another honor code — that whatever is shared in the circle stays in the circle, while acknowledging the mandatory reporting requirement regarding physical and sexual abuse.

McNair asked for a check-in, a one-word description of how each student was feeling. The talking piece made its way around the room. Tired. Confused. Bored. Relief. Exhausted. Hungry. Curious. Relaxed. Experience tells McNair that these lackluster responses will soon evolve into deeply revealing, moving, compassionate moments that transform casual relationships to ones that inspire and move them all.

Soon students will be asking for a circle. “They say, ‘I have some stuff I have to get off my chest.’ In one circle, we talked about friendships and the qualities of a good friend. A young lady who was rarely in class and always alone, said trustworthiness.

“As we went around the circle the talking piece came back to her. Through tears, she told us of a heavy burden in her personal life. Students who had paid little attention to her suddenly understood her pain and responded. Now they knew why she wasn’t in school; why she was isolating herself. They were filled with empathy, compassion, and understanding and they extended it to her. She started coming to class and her friends are still beside her.”

This opening of students’ hearts and minds, and the relief of stress and burdens, helps bring students a certain peace, McNair said, the kind of peace that makes their time together as a community valuable — instructional time included.

The transformation is not lost on McNair. “I’ve learned to reflect on my own responses to students’ issues and I am a better teacher for it.

“I’ve learned that a student may not be doing homework because he is babysitting his younger siblings, including cooking dinner every night. I’ve learned that students are being watched by their single parent’s boyfriend or girlfriend and not getting attention at home. For an emotionally developing student, these issues are big. So while fairness is fundamental, my fairness matches the individual student because I know them.”

DeMarco, now a sophomore, said McNair’s circles improved his self-esteem. “Her classroom felt like a family to me. It was a place where I could share some things with my classmates that really bothered me — it was definitely a safe place,” he said.

“In our circles,” said Marquette, also a sophomore, “we found out our classmates were going through things at home that were really deep. The peace circles allowed us all to release stuff that we couldn’t get out anywhere else — things that we just hadn’t been able to talk out. It got better because we all talked about it together and tried to help each other.

“Some students are really looking for an opportunity to release the stress they have. If we all started doing the circle, I think it would make our community a better place.”

Resources

Safe Saner Schools — Whole-School Change Through Restorative Practices; Center for Restorative Process — Conflict Inquiry and Community Transformation; Student Peace Alliance — Resources for Dialogue and Conflict Resolution; Restorative Works Learning Network