Across Three Centuries, MSEA Labor Activism Makes Gains for Educators and Students

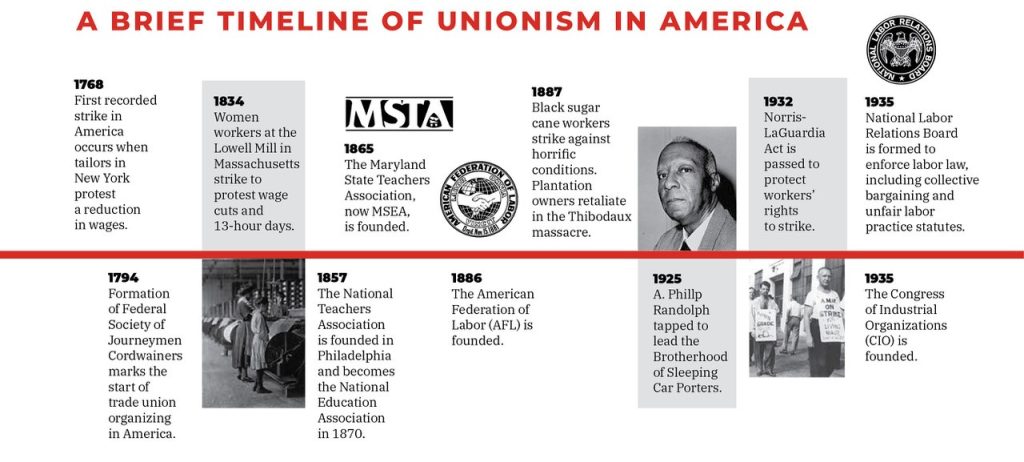

September is highlighted not only by back to school, but by the celebration of Labor Day, which recognizes the hard-won battles by unions to obtain meaningful reforms and respect for workers’ value to the U.S. economy. It reminds us that the story of labor is also MSEA’s story. Labor union leaders rose to strength out of oppressive workplaces to give voice to the voiceless, equity to the oppressed, and rights to the disenfranchised. Likewise, MSEA has fought to empower educators, long before they had collective bargaining rights, and to deliver education equitably throughout Maryland public schools since 1865, when it was formed as the Maryland State Teachers Association (MSTA). The collective voice of Maryland educators—and organized labor in general—has come a long way since then.

Labor in America: Early History

The first recorded strike in America was in 1768, when New York City tailors protested a wage cut. In 1834, women workers at the Lowell Mill in Massachusetts bravely protested grueling 13-hour days, the first of many protests led by women. In 1887, the protests of Black workers against the living and working conditions of Louisiana’s notorious sugar cane plantations were met with a murderous mob of white owners who killed 60 farmworkers. It would be years before national labor reform would come about and longer for equal representation for women, immigrants, and Black and Brown workers.

National labor organizing advanced in large part due to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and its president, Samuel Gompers. Gompers, an immigrant from London who followed his father into the cigar-rolling trade, led New York City’s Cigar Makers International Union from 1875–1896, and then helped found the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU). The FOTLU reorganized as the AFL in 1886, with Gompers elected as president, a position he kept for almost 40 years.

Gompers’ vision of labor unions was threefold: 1) restrict union membership to wage earners, not a more community-based organization open to employers as the Knights of Labor (an earlier reform effort) allowed; 2) a “pure and simple unionism” focused on pragmatic concerns like wages, hours, and grievance procedures; and 3) political non-partisanship—mobilize members around parties and candidates that support the union’s agenda.

During the rise of the AFL, landmark strides were made in legislating workers’ protections. The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 gave employees the right to strike and boycott. In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act provided basic worker protections like minimum wage, overtime pay, and basic child labor laws.

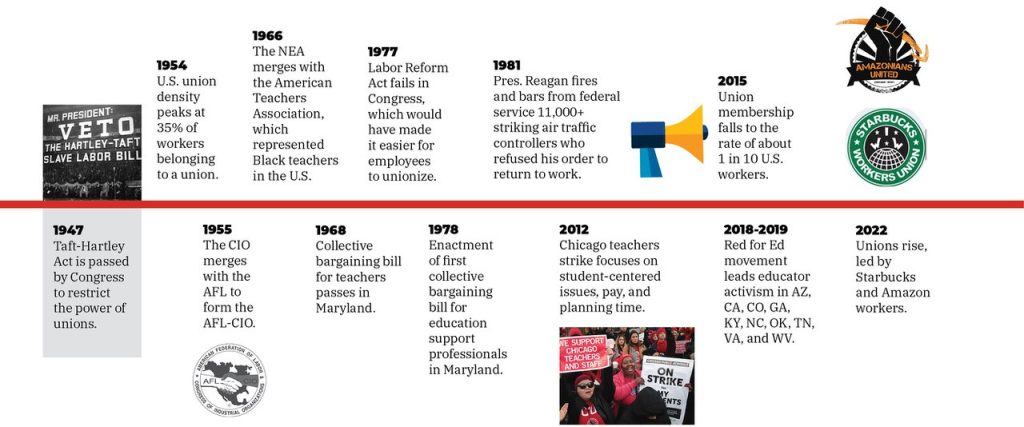

The powerful AFL and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) merged after years of bitter rivalry in 1955. The CIO was founded in 1935 and, while leadership and many skilled construction and industrial trades jobs remained out of reach for minorities and women, the CIO actively organized industrial workers no matter their race or heritage, according to the National Archives Prologue Magazine article “African Americans and the Labor Movement.”

The CIO undoubtedly influenced the new AFL-CIO’s role in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1965. In 1960, then president of the AFL-CIO George Meany said, “What we want for ourselves, we want for all humanity” and soon sought counsel from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on how they could work together. King proposed investing the AFL-CIO’s pension assets in housing to lessen economic inequality. The AFL-CIO then established an Investment Department to guide union pension funds to be socially responsible investors. The AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust was one of the first socially responsible investment funds in the U.S. and now has assets of more than $4.5 billion.

While Gompers and the hard work of labor organizers and theorists paved the way for organized labor, well into the 20th century these unions were made up mostly of white men—American born and Protestant, skilled in the trades, and able to pay union dues. Blacks, women, and many immigrants were excluded. It was the cigar makers in 1867 who first welcomed Black and women workers, and in 1912, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers began to accept women as telephone operators. And in 1925, A. Philip Randolph was tapped to lead the all-Black service staff of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; 10 years later they won the right to collectively bargain.

Randolph was just getting started in his fight for Black workers. In 1940, President Roosevelt refused to issue an executive order to ban discrimination against Black workers in the defense industry. When Randolph threatened to organize 100,000 “loyal Negro American citizens” to march on Washington, Roosevelt capitulated and issued the order, which stated: “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” Later, Randolph forced Harry Truman to end military segregation by threatening to hold the Black vote. In 1963, he was made chair of the March on Washington.

Maryland Educators Organize

A century earlier in Maryland, in 1866, Maryland educators founded MSTA, nine years after the national precursor to the NEA formed. It was the 27th state to establish a teachers union, and, as in the other states, MSTA began as a part-time organization without staff. The state associations shared a common purpose: to improve educational conditions and to establish unity and camaraderie among educators.

In 1900, MSTA’s new constitution limited membership to people “actively engaged in educational work,” including administrators as well as classroom teachers. In the 1920s and 1930s MSTA followed the example of the national association by adopting more democratic practices and explicitly supporting social justice. In 1921 MSTA adopted a new constitution that changed the annual meeting to a representative assembly (RA), which still meets at least once annually today. Predicting the equity work that continues now a century later, in 1922 Maryland’s education law, which MSTA was involved in working on, addressed equal education opportunities for children in poorer counties.

In the 1940s, MSTA prepared for post-war dynamics and a changing education landscape, as researcher Benjamin Ebersole found. In 1943, at the RA members took action to strengthen the association’s democratic foundation, authorized setting up a headquarters and hiring a full-time executive secretary, and established an advisory council. This positioned MSTA to develop a robust legislative program. The council members included the president, first and second vice president, and one elected member from each of the 24 local teacher associations (Baltimore City included).

MSTA’s public profile consciously expanded during these years as well. In 1943 the council published the first issue of The Maryland Teacher, a periodical to inform the public as well as members about important education issues. The first edition included MSTA’s seven-point platform, which built the foundation for a strong union:

- to unify and strengthen the teaching profession throughout the state

- to furnish teachers a statewide medium of professional experience

- to furnish dependable information and data to all the teachers of the state

- to present to the public a clear interpretation of the schools

- to act as a clearing house for the various local associations

- to constitute a strong bulwark against selfish pressure groups which would undermine the effectiveness of the public schools

- to work consistently for the welfare of the teachers and pupils of Maryland

In 1944, MSTA hired its first executive secretary (part-time until 1945) and established headquarters in Baltimore. MSTA positioned itself to tackle “unprecedented problems and dynamic growth in education and all areas of society,” Ebersole found.

In the mid-1940s, annual conventions began to reflect growing membership. By 1949, the attendance was near 10,000, making MSTA’s RA one of the 10 largest state teachers’ association meetings that year. MSTA’s RAs demonstrated a deep concern about national and international issues. The meetings featured expert speakers on topics as varied as war, extreme nationalism, post-war recovery abroad, and proposed laws on subversion designed to intimidate teachers.

The Maryland Teacher emerged as one of the primary association functions in this decade. The journal featured curricular concerns, coordinated communication among members, and informed the public about curricular and educator matters. In 1944 an article in the publication discussed lobbying to make it more accessible and palatable to members, explaining that lobbying is not unprofessional, but essential to the process when opposing groups are lobbying against public schools’ best interests. “Teachers must therefore be organized, in the good American spirit, to ‘play politics,’ not unethically or selfishly, but in an enlightened manner” in the interest of equitable education for all students, the magazine stated. That year MSTA developed an education plan for the legislature’s consideration: It sought smaller class sizes, a uniform 12-year education program for students, policies to encourage future educators, a teacher salary schedule, and a better library service statewide. Included in the successful legislation was a new salary scale, the equalization of salaries for white and Black school superintendents, and expanded vocational education for students with special needs.

In 1947, MSTA was instrumental in developing and getting passed into law a comprehensive plan that fundamentally transformed and improved the educational program, making Maryland a national exemplar in public education. Through 1949, legislative victories followed, setting better starting salaries, addressing working conditions, and improving educational opportunities and equity. At this time MSTA began to publish names of supportive legislators in Maryland Teacher.

The executive secretary became a full-time position in 1945 and had the responsibility to organize and support the local associations and to “interpret to the public the work of the association and the problems of the schools,” Ebersole noted. A more democratic method of selecting candidates for the executive committee was established in 1948. The adopted straw ballot method allowed general members to have greater say in the candidates for three members-at-large on the executive committee.

Between 1949 and 1956 MSTA advocated for improvements to the teachers retirement system, set minimum teacher salaries and increases, set class sizes, sought workers compensation coverage for teachers, and organized to defeat the anti-subversive act for being “authoritarian and without adequate protection for persons accused.”

In 1951, three years before the U.S. Supreme Court ruling desegregated schools, in a nation still riddled with racism and Jim Crow laws, MSTA removed the word white from its constitution’s reference to membership requirements and merged with Maryland Educational Association, formerly the Maryland State Colored Teachers’ Association. Prior to that time, Maryland’s educator unions—like its schools at that point—had been segregated. The integrated association took action at MSTA’s 1964 RA to pass a resolution recommending a statewide program to provide instruction for all, regardless of age, race, creed, physical or intellectual ability.

In the 1960s, MSTA lobbied for the state to address a teacher shortage, lauded changes in certification requirements to raise professional standards, advocated for a duty-free lunch, sought new minimum salaries, and approved a policy for professional negotiations “to establish with boards of education ‘a climate conducive to dispassionate consideration of mutual problems and goals.’”

While all this work was going on, collective bargaining and labor rights were evolving separately among different industries across the country. In 1926 the Railway Labor Act applied only to railroad workers, and when the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) was enacted in 1935, it excluded public-sector workers, such as educators, from the right to collectively bargain. The door was not open until 1962, when President Kennedy signed an executive order granting federal employees the right to bargain. Public-sector unions were empowered to pursue collective bargaining for teachers and other educators, state by state. The ability to collectively bargain opened new horizons for educator voice and strength in Maryland, with collective bargaining laws for teachers passing in 1968 and for education support professionals in 1978.

The Big Picture of Labor: 1960s to Today

Nationally, labor union membership peaked at about 35% of workers in 1954, and now hovers at about 10%. Unions, once the watchdog of a rising middle class, suffered in the late 20th century. The middle class floundered as blue-collar jobs and manufacturing were outsourced to cheaper labor in other countries. Those types of steady jobs have not returned; nor have they been replaced. Many working class families, once thriving and moving up the ladder of education and wealth thanks to the bargaining power of union members, were left looking for work, falling victim to despair and all that comes with it.

Educators’ unions, however, remained large, influential, and organized. And indeed, educators emerged as labor leaders of the early 21 st century. A pre-pandemic Red for Ed wave of educator activism in 2018–2019 preceded further educator activism around the nation—from West Virginia to Arizona, California, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and elsewhere. Organized educators struck a nerve in workers across the country. Unions were in the news—stories, photos, and memes showed emboldened workers. Suddenly, people who looked like your child’s teacher, your mom, your dad, your sister or brother were marching, shouting, carrying signs, and wearing loud t-shirts. It looked like something you could do. In fact, it looks a little like educators schooled Americans on how to take control of their working life, using grassroots organizing, public pressure, and worker-to-worker conversations to stand up to inequities and unfair systems. In the past few years, workers—at places like Starbucks, Amazon, and UPS—and unions across the country have highlighted the need for a strong voice, enhanced transparency, and improved fairness. Today, polling shows sky-high approval ratings for unions across the political spectrum and especially with young people.

These trends were echoed in Maryland as well. In the second half of the 1960s, MSTA strengthened its legislative and union power. In 1966, the RA amended the bylaws to authorize a $1 million fundraising campaign for teachers’ rights; and in 1967, MSTA celebrated the passage of a duty-free lunch for teachers and formed the Maryland Educators for Good Government, political action committee (PAC), the forerunner to MSEA’s Fund for Children and Public Education PAC. In 1968 the Professional Negotiations Act, developed by MSTA committees, passed; the School for Negotiators was created, and the RA adopted the NEA Code of Ethics for the education profession.

Organizationally, the second half of the 20th century saw MSTA take steps to increase the democratic characteristics of its elections, advocate for better and more equitable school funding, and defend a secure retirement for educators. The union also grew, expanding membership to education support professionals in the early 1990s and to community college employees in the last few years.

The beginning of the 21st century saw MSTA (soon to be MSEA after a name change in 2009 meant to reflect the full breadth of the association’s membership) leading the way in organizing for equity, school funding, and social justice issues. In the early 2000s, the association championed the Thornton Bridge to Excellence Act to address the chronic, historic disparities in funding and resource allocation between high poverty schools and others in more affluent communities. MSEA also played important roles in supporting successful ballot measures defending the Dream Act and marriage equality in 2012 and in ensuring that casino revenues would go towards increasing school funding in 2018.

When the state failed to fully fund the Thornton program, and the gap separating the high poverty schools from others widened, MSEA took part in the Red for Ed wave sweeping the nation by organizing to fight for the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future. A huge rally in Annapolis, years of school building and community meetings across the state, and countless lobby visits helped to deliver a new funding formula that will increase education resources over a decade to achieve greater equity for all students, support and require high quality educators, expand career and technical education, and make pre-kindergarten accessible to all 3- and 4-year-olds.

Strength in Unity

Democratically, MSEA has organized and coalesced power for the good of members and students. Whether through MSEA’s long-time and successful efforts to lobbying for pro-student and pro-educator laws and policies in Annapolis or through following AFL President Gompers’ vision of scrutinizing and interviewing political candidates to determine alignment with educator and union values, MSEA members have played an influential role in education politics and policies in the state.

Strong unions don’t just deliver a stronger voice for workers; the Economic Policy Institute has long documented the positive effects of unionization on workers in general and union members in particular. Union members earn better pay, health insurance, and other benefits. Women and people of color especially gain from collective bargaining because it reduces wage inequities. Moreover, unions and their members tend to be more engaged in civic involvement and support progressive policies including increased education funding. Union achievements reduce inequality and provide more opportunity for workers and their families.

MSEA continues to fight for the rights of education employees, whether through campaigns for improved school funding and strong contracts, through our ESP Bill of Rights campaign—demanding a living wage, improved working conditions, greater respect, and more for education support professionals—or through victories for fairness and transparency for workers like the establishment of the Public Employee Relations Board during the 2023 legislative session.

MSEA’s ongoing campaigns and work are built on nearly 300 years of labor activism. A direct line connects MSEA’s beginnings in 1865 to Labor Day 2023 and beyond.

Parts of this story are adapted from “Unions Rising” from the June 2022 edition of ActionLine. Additional details are from MSEA and NEA records as well as “A History of the Maryland State Teachers Association,” Benjamin P. Ebersole, dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, 1965.